The Real-Time Internet War

The first Gulf War was described as the first to play out in real-time in the mass media; the War in Ukraine is the first war that’s…

The first Gulf War was described as the first to play out in real-time in the mass media; the War in Ukraine is the first war that’s playing out on the real-time internet: Twitch, TikTok and Twitter.

Although there have been other conflicts in the past decade, this is the first where there’s widespread availability of real-time streaming platforms and the war is taking place within a modern democracy equipped with pervasive use of mobile technology.

The result: a dynamic ecosystem in which people record videos of enemy locations, combine it with other real-time information sources. This creates a cycle of unprecedented information that aids Ukrainian defenders through morale-building memes, improved international opinion, financial support and direct operational intelligence in support of freedom fighters.

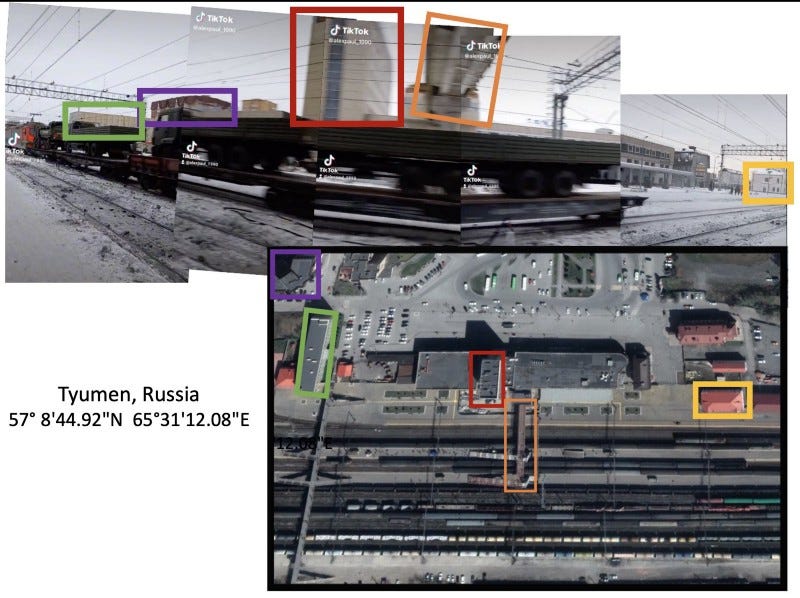

Crowdsourced Intelligence

It starts with video recordings of troop movements, like the widely-circulated video that’s on Twitter:

That’s when crowdsourced intelligence plays a role. Consider what happened in the Boston Marathon bombing in 2013, when pervasive video recordings and photographs quickly resulted in the identification of the perpetrators. At the time, NBCNews noted how helpful the Internet was to the investigation:

“The Internet is a force multiplier,” Lenny DePaul, the retired former chief inspector of the U.S. Marshals service, told NBCNews. “We can’t knock on one million doors, so the speed of the Internet is a major advantage when it comes to sharing information.”

In the invasion of Ukraine, this has expanded to country-wide scale. @Cen4InfoRes on Twitter maintains a map of conflict locations with links to videos, incidents of human rights abuses, and troop movements:

This information can be aggregated with real-time data from sources like FlightRadar24:

And ship locations on MarineTraffic:

And real-time traffic data on Google Maps:

Geolocation and Photo Integration

Information from TikTok videos and map data can be used to authenticate troop movements and combine with input from vehicle identification experts, such as this example from Cen4InfoRes:

This can also be used to identify the deployment of weapons of mass destruction, such as the Iskander missile system being deployed in this photo:

The Iskander missile system has a high potential for widespread civilian death — war crimes — and documenting these is going to be critical to holding people accountable in the aftermath of the war.

Signals intelligence, which is key to understanding supply lines and movements, is also being integrated into the crowdsourced intelligence matrix, such as this intercepted Russian military communication:

Supporting Defenders

What’s the result of this unprecedented level of crowdsourced intelligence? Perhaps more outcomes such as this:

Internet Access

In the early stages of the war, Russian attackers attempted to destroy access to mobile internet. However, recent deployment of the Starlink network may mitigate destruction of the ground-based internet systems. Starlink operates from a network of thousands of satellites at only 210 miles, called “very low earth orbit” (VLEO). This allows Starlink to provide internet access at very high speeds and low latency.

Semiconductors

The US sanctions include an embargo of chips based on US technology. Russia only accounts for $50B in semiconductors in a $4.5T industry, and gets 70% of its chips from China. These Chinese chips are not advanced; they’re useful for automobiles and cheap home electronics, but not advanced computers — especially not the sort of chips needed for artificial intelligence and cloud computing. Although this won’t have an immediate impact on Russia, cutting off their supply of these chips will put them at a further disadvantage for conducting intelligence and counterintelligence operations in future conflicts — especially those where crowdsourced intelligence plays a role.

Decentralization and Centralization

Russia can’t control the internet as easily as China—but they’re trying to use legal structures to force tech giants like Meta and Google to comply with their censorship laws. This will help support Russian agitprop campaigns and suppression of information regarding the truth of events happening outside their borders.

This demonstrates a risk of any centralized platform: each one provides a centralized vector of attack (whether through physical force, or through legal assault).

Decentralization is more resilient; the Internet itself is decentralized, which means that independent websites are harder to suppress than large platforms.

Financial Systems

Decentralization does show a two-edged sword. On the one hand, the ability for central bankers to shut off Russia’s access to the SWIFT system has been described by some as a “financial neutron bomb:”

Decentralized financial systems like Bitcoin are harder to control. Decentralized exchanges (DEXes) operate with smart contracts between the participants, rather than a central company that can easily control access. But centralized exchanges (CEXes) connect with payment gateways, and that’s where governments have control. That’s why Ukraine’s Vice Prime Minister Mykhailo Fedorov asked the exchanges to prevent Russian oligarchs from funneling their money through them.

The other side of the sword is that the decentralized nature of cryptocurrencies has also been a means of support to the Ukrainian army:

The above address is an official post from the official Twitter account government of Ukraine. Do not use any other addresses if you wish to make a donation. There are a lot of scammers hoping to steal your crypto.

Of course, the flow of cryptocurrency into the Ukraine army is supported by a widespread online campaign of memes, PR and information. Which leads to:

Memetic War

Mythologizing and propaganda has always been an aspect of war; heroes bring morale to troops and embolden the civilian population that supports them. Propaganda was used through World War II to influence public opinion — leveraging the mass media to do so. In the age of social media, where content propagates through memes and

Memes compress information down to its essentials and package them into easily redistributable forms. Both sides are fighting the memetic war, but Ukraine is clearly succeeding. Although the Kremlin had a highly-skilled network of meme warriors in their past episodes of attempted election interference — they lack the coalition of sympathetic supporters in this situation to provide a sufficient environment for propagation.

Instead, they’re clumsily attempting a social media narrative that their military failures thus far (including what appear to be substantial losses of infantry and materiel) are actually because they are amazing humanitarians, the result of their desire to limit civilian casualties:

Any search on Twitter for “russian limit civilian casualties” will result in a various Kremlin shills reproducing this narrative almost word-for-word, and generally failing to garner support.

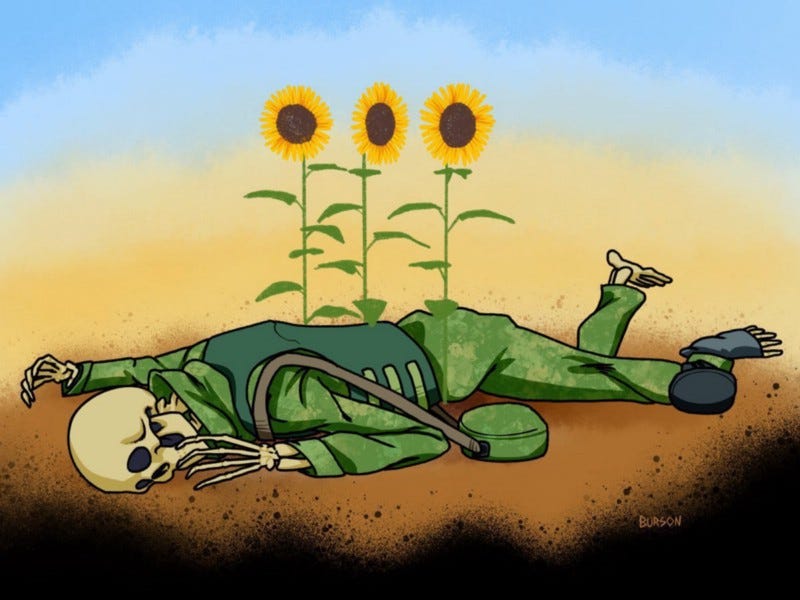

Contrast with Ukraine, which is quickly leverage powerful messages into memes. This video went immediately viral on social media such as TikTok and Twitter:

And in days, the sunflower video has turned into imagery like this:

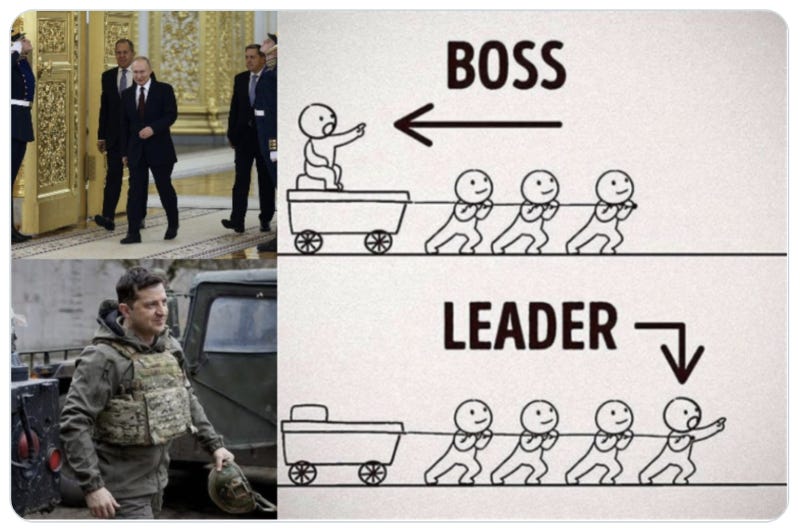

Or memes that focus on the heroic nature of Zelensky, compared to Putin:

Why do these memetic messages matter? Morale. Morale is a huge factor in determine whether a force will rout or put up a fight. History shows plenty of examples: the complete lack of morale in Afghanistan — compared to the impressive morale of Japanese forces in World War II. For a very detailed discussion of how core beliefs — supported through propaganda cultural practices — can dramatically affect the way soldiers fight in war, listen to Dan Carlin’s Hardcore History series Supernova in the East, which explains how substantial this was in the Pacific theater of WWII.

Memes and Disinformation

Memes can also spread disinformation and mythology. A widely-circulated video on social media purports to show a Ukrainian ace fighter pilot taking down a Russian plane — but is actually taken from a videogame:

But that hasn’t stopped Ukraine from mythologizing the “Ghost of Kyiv” anyway; their video focuses on the heroism and the the story to inspire their defenders:

Is the Ghost of Kyiv a real person? Maybe, maybe not — but the spirit of the Ghost of Kyiv is what they seek to imbue in their freedom fighters. He’s an unkillable symbol.

“Russian Warship, Go Fuck Yourself”

Do symbols matter? Do they influence behavior?

Another widely-circulated video contains audio from the border guards being challenged by a Russian warship. They refuse:

But more importantly, the video may be impacting behavior. Here’s a Georgian captain invoking a similar line in his refusal to refuel a Russian ship:

Rallying cries are a powerful thing. And in this first war that’s truly playing out on social media — rallying cries spread at the speed of the internet.

Social Media: Education

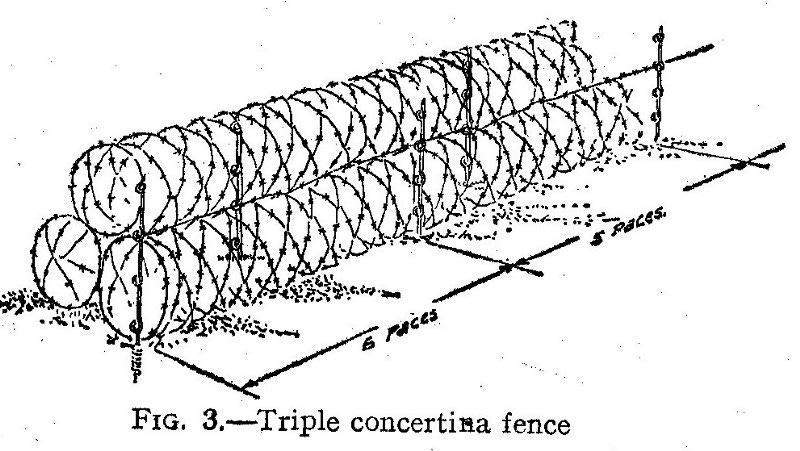

Social media is more than memes: it is also a place for education. John Spencer is sharing information for urban defenders to inflict massive casualties on invaders and sow chaos amongst the enemy:

Journalists, everday citizens and crowdsourced intelligence experts are meeting in realtime on social audio platforms to share information with each other, such as this one hosted by Peter Corless:

Those who support the Ukrainian side are also guilty of spreading disinformation. Here’s a Ukrainian citizen showing how to drive a Russian tank. It is just general instructions, as it doesn’t appear to be a tank “abandoned” by the invaders — but it gets spread far and wide because people see it as an example of Russian incompetence. It’s easy to fall prey to confirmation bias and spread something that supports your views, just as I did when I first shared this video:

Further Reading

War is highly unpredictable and rapidly changing. Because of this, I’ll keep updating this article as the situation evolves. If you wish to keep tabs on updates, please follow me on Twitter here.