Unbundling Digital Identity

Unlocking new ways to work and play

This article on digital identity originally appeared on a16z Future blog

Who are you when you’re online? This question is all the more important as we spend more and more of our lives there. In the past decade, online usage has more than doubled; for GenZ, it’s even greater. How we spend that time has also changed as the early, transactional web has expanded to a wider range of experiences that are creative, social, and interactive. As a result, our lives are often defined more by our digital identity than our physical one.

But many of us don’t have a single online identity. Just as you might highlight different aspects of yourself on a date than you would on a job interview, your presentation of self in an online game may significantly differ from the one on social media.

This is a problem I’ve been thinking about and working on for years, both as a longtime gamer as well as a founder and builder in games dating all the way back to the dawn of internet gaming with Legends of Future Past. In the years since, I’ve built games based on beloved franchises such as Game of Thrones and Star Trek. I’ve supported hundreds of game developers at Beamable, where I’ve participated in the coevolution of digital identity and online creativity.

As digital identities — which incorporate not only our credentials and data but also our outward expression and relationships — developed from their early iterations on forums, chat rooms and online games, they became bundled by a handful of tech corporations. But now new technologies are emerging to unbundle our digital identities and reconstitute them in fresh ways. From my vantage point in games, this is happening particularly quickly with avatars and new platforms that accelerate game development.

This unbundling and rebundling of digital identity benefits both users and creators. Users can have greater control and better reflect how they see themselves and how they wish to be seen. Creators and builders, meanwhile, now have more efficient paths for how they design and conceive of games: tiny teams can now launch games built in sophisticated, immersive worlds without the burden of complex infrastructure or dependence on centralized platforms. In this piece, I’ll share how digital identities have evolved, where they could be going, and how both users and creators might benefit.

The bundling of digital identities

Today, digital identity refers to all of the manifestations, relationships, and data about your presence online. But at the beginning, digital identity was simply an account with a username and password to limit who was able to use the network and segregate access control over files.

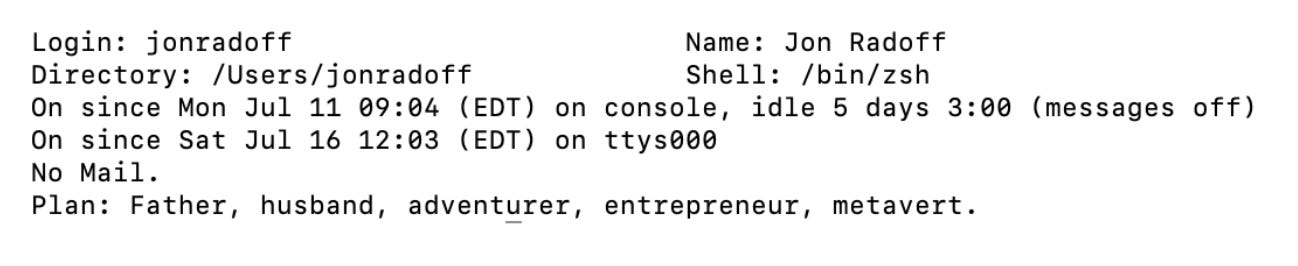

Once you had multiple people accessing the same computers, they started storing information about what they were doing — and even who they were. A good example of this is the finger command on Unix, which displayed information about you, including the contents of your ~/.plan file:

The original intention of the Plan was to provide a text description of what you were working on. But if you peered into early Unix systems, you’d find everything from Zen koans to Lord of the Rings quotes to egg salad sandwich recipes. People used the Plan to express themselves. It was like taking a driver’s license and adorning it with decals.

On the internet, meanwhile, an early messaging system called Usenet provided a shared space for self-expression. Outside the internet, bulletin board systems (BBSes) and online services like America Online provided moderated environments for messaging about shared interests. Early online games such as multi-user dungeons (MUDs) and “door” games let people begin to play with identity by taking on different roles and personas.

One can start to see the throughline to the age of social media, the appeal of which relies on people’s desire for not only self-expression but also interaction. A byproduct of social media’s ubiquity, however, was the bundling of multiple online identities. The invention of Google Login and Facebook Login — ostensibly to make it easier for consumers to log on and help individual websites increase conversions —resulted in a massive improvement in the user experience for many websites and a valuable set of data for advertisers. But it also contributed to a merging of disparate digital identities.

The rise of multiple digital identities via avatars

A recent survey of GenZ social media users in Hong Kong found that 65% of them prefer to use an avatar — a character or image that digitally represents the user — online rather than a “real” identity. The reasons for this are varied, but it is likely a combination of wanting to compartmentalize identities, curate the way they are perceived online, and play creatively with different personas.

The first aspect, compartmentalization, happens because people don’t want to link all their different social contexts and networks together. When you’re in an online game, you present one version of yourself (perhaps a pseudonymous champion for the Horde along with video captures of your recent raids). On LinkedIn, however, your professional profile tells the story of your career, along with articles and videos that communicate your expertise.

With regards to the second aspect, we curate different versions of ourselves even within specific networks. It’s why people create multiple TikTok, Instagram, or Twitter accounts: to brand themselves closely to specific content niches, secretly engage with certain hashtags, or avoid discrimination. The desire to curate one’s online identity is also driven by creativity: the logical extension of one’s fashion choices and personal grooming in an online world where you are no longer limited to “one body, one identity.”

In online games, people create alternate characters (“alts”) to try out different play styles or adopt different personas. This gives people an opportunity to experience the world from different perspectives. Recent data shows that a third of men prefer playing as female characters in online games. (I play both male and female characters, and I met my wife in an online game while I was playing a female character.)

When people lack the tools to create the version of themselves they want, they tend to rebel. It’s why fake Instagram accounts, called “finstas,” exist. And it is one of the reasons why Meta decided to decouple its Meta Quest platform from a dependency on Facebook Login. In the latter case, people primarily use Quest for games and immersive social experiences; they want the freedom to express themselves and form game-specific friendships in these environments without feeling forced to link their identity to the platform they use to wish Uncle Frank a happy birthday.

Taken collectively, avatars give users more options for self-expression. And the possibilities are becoming more advanced, benefiting both users and developers, who can tap into new infrastructure for their games. Take Metahumans, from Fortnite publisher Epic. It’s a photorealistic character system built upon accurate simulations of skin, hair, muscle, and skeletons that allows you to appear as an idealized version of yourself — complete with the outfit, hairstyle, body and face you prefer. Likewise, in the future “voice fonts” could modify your speech to match how you’d like to be heard — including removing (or adding) accents, adjusting pitch or changing gender. Real-time translation software could even be incorporated to make it possible to interact across language boundaries.

Composability

A common critique of avatar systems in the past was that consumers didn’t want them. Indeed, platforms such as Xbox had relatively limited success, with players often complaining they were too cartoony or didn’t get used in many games beyond the most casual. However, times appear to be changing. You can witness the beginning of this inside Roblox and VRchat, where you can take your avatar with you across countless games, worlds and immersive experiences. Here, your avatar is central to your experience rather than a side feature. Why is this change happening? It is likely the confluence of mass-market creator economies like Roblox, which have made it much easier to compose experiences, and the increasing importance of digital identity for younger generations that have grown up with virtual worlds and virtual property.

The next step beyond this is the rebundling of your identity so you can transcend walled gardens, transporting your chosen identity into other worlds that share a common framework.

While many of these experiences will be games such as those already found in Roblox, a fertile area for innovation is within experiences combining self-expression with a shared social context. Imagine attending an online music concert — which is increasingly taking place within game worlds. Unlike a recording, a live experience is about the conversation between performer and audience. Part of that conversation involves you actually being present in the virtual space, reacting in real time, and expressing yourself both through your avatar’s appearance and through your behavior. Further, if you visit the merch table and collect a token of your attendance, it can be incorporated into your avatar, synthesized into your identity, and taken with you to the next online experience you attend. The memory of the event will be forever bonded with how you interact and present yourself online.

This desire to incorporate memories, events, and fashion statements into your online identity has not been lost on traditional brands. It’s why Burberry licensed content into Blankos Block Party, a gaming universe created by Mythical Games, or why Balenciaga created fashions for Fortnite. And it’s why a new digital-native brand like RTFKT was acquired by Nike. The rebundling of identity into avatars will involve taking fashions, animations, styling, and participation tokens from one experience to the next.

How to make it happen

One challenge is how to solve the “cooperation problem.” How can we get companies as varied as Disney, Universal, Epic Games, and Production Club to create — or even just allow for — a way for our avatars to be brought into different experiences?

One way would be to just let Microsoft, Meta, or Sony figure it out for us. But that may not benefit creators, who would end up being locked into the same sort of creative and economic constraints that go along with things like Facebook Login.

These real-world and digital-only experiences will need a way for us to take our avatars with us using protocols that do not depend on control by specific authorities. That’s where web3 plays a role: the inherent composability of blockchain provides an open environment for recording the definition of your avatar and taking it with you into unrelated environments. TraitSwap shows how this could work with 2D profile-picture avatars: It ingests the metadata for an NFT you own, swaps traits around, and lets you integrate branded elements into a new avatar representing your composition. Platforms like Ready Player Me provide a combination of a customization marketplace and an interoperable avatar system that allows avatars to be imported into unrelated worlds.

The “key” to your avatar, then, may become a digital wallet. The inherent decentralization of the internet shows us the way: a system similar to the domain name system that’s used to map host names to an IP address may become a method of identifying individuals. Protocols like the Ethereum Name Service (ENS) use the immutability of blockchain to provide a decentralized means of associating names with owners.

ENS demonstrates how the new identity bundles might look. Instead of storing your identity in a centralized service, you retain your own private key to a digital wallet. The public address of the wallet is mapped to a canonical name (such as “jradoff.eth”) so your friends don’t need to remember your hexadecimal wallet address. To log in to a service on the internet, you “sign” a request, which uses a cryptographic algorithm to prove that you are who you say you are.

When composable identities and digital wallets become commonplace, creators will be empowered to craft you-centered games, worlds, music and theater experiences without needing to build complicated avatar and login systems from scratch. Beyond the technical advantages, it also allows users to reinforce and build upon the emotional bond with the identity they present through their avatar. Independent creators and game-makers benefit from the investment people make in identity, retaining more of the value in their own creativity, without the dependencies and rents owed to a centralized platform.

Furthermore, creators can overcome some of the inherent problems of creating online worlds: Rather than depend entirely upon business models of continuous re-engagement, they can instead offer you new content that you’ll bundle back into your avatar. For example, when Twenty One Pilots launched a concert in Roblox, a set of items to customize your avatar were connected to the concert that you could take with you into multiple games. The result is that the value created in the concert outlived the event itself. A decentralized system could extend these proofs of participation and customizations beyond any one ecosystem.

This inverts the typical model of experience creation such that a temporary moment becomes inscribed upon your avatar, boosting its perceived value and enhancing your self-expression. The expressions become as personal and persistent to you as a music playlist.

A common critique of shared-avatar systems is that they’ll lead to a jarring clash between the intended artistic experience of a creator and the expression they’ll have online. But just because an avatar system is open doesn’t necessarily mean that it’s unregulated. One way to think of this is that an avatar provides a system of defaults that can be overridden depending on an individual world’s rules: If my Starfleet costume isn’t allowed within a Star Wars experience, then it might revert to an appropriate style. Object-oriented software development has dealt with inheritance, composition, varying privilege levels, private vs. public attributes, and polymorphism for decades. Avatar systems will build upon that know-how.

The rebundling of identity

These emerging technologies create simplicity for world-builders, enabling an exponential increase in the number of creators. The trend has already begun: Observe the accelerating volume of modding, in which individuals build off the core experience of a game system and add their own unique experience on top. One finds this extensively in Minecraft, Roblox, and smaller games from Terraria to Undertale. Modding demonstrates the creative impulse many individual gamers share, something that began at least as early as the storytelling in tabletop Dungeons and Dragons.

The new generation of builders is interested in shaping the metaverse through game creation, modding and world-building — along with how they project their identity into digital space. Their motivation is to express themselves, craft experiences, and connect with other people on their own terms. They care about identity and expression, not technology and infrastructure.

What began as a means of authenticating ourselves to computers and applications has evolved into a means of self-expression. Digital identity is no longer singular. We will take different identities with us into different experiences, sometimes retaining continuity across different experiences and sometimes maintaining identities unique to a particular world.

These changes require better technologies to support privacy and security — while also supporting user choice, usability and interoperability. While the challenges ahead are substantial, the rebundling of identity into a you-centered internet is one that will enhance self-expression, both in terms of our presentation as digital humans and our ability to craft worlds and experiences for others.

Further reading

To enable interoperable self-expression, avatars need composability. My article, Composability is the Most Powerful Creative Force in the Universe, provides background on how this is taking place in a range of situations, from open source to game-making to computational architectures.

David Bloom’s article Going Live and Immersive Is The Next Frontier for Musicians, Movies, Artists and More is a good introduction to the types of real-time experiences (beyond games). This is the context for the rebundling of identity into avatars.

Ben Thompson’s The Great Unbundling covers how technology has reshaped the way media is packaged, presented, and organized online.

The Private Life of Generation Z gives a good summary of how the generation that has grown up with pervasive online services is also thinking differently about privacy, identity, and avatars.

The Pseudonymous Economy by Balaji Srinivasan is a good introduction to how identities can gain value without being connected to a real-world identity.