Why Scaling Games is Hard

NOTE: this was a post I previously shared through the LinkedIn newsletter system. I’ve since moved to Substack, and this content is here as part of my archive.

Welcome to the inaugural post of Scaling Games. Here, I'll be writing about all the things that go into prototyping, shipping, and then operating a successful game. I'm writing for game developers, game entrepreneurs, studio heads, as well as gaming investors and stakeholders.

For those who are familiar with my work in the Building the Metaverse blog, this is going to be more focused: everything here will be about games: making things fun, and then making them big. We're going to get into things like business issues, creative leadership, workflow, live operations and the nitty-gritty of technologies.

To kick things off, I'm going to repurpose some content from my blog that provides a bit of context for the things we'll be talking about here.

Context for Scaling Games

In 2021, there were over $85 billion in deals invested into the game business. We've already surpassed that in the first month of 2022.

With all this capital entering the market, it’s getting more competitive than ever. That means it is harder than ever. What makes it so hard?

Sustainable Game Business

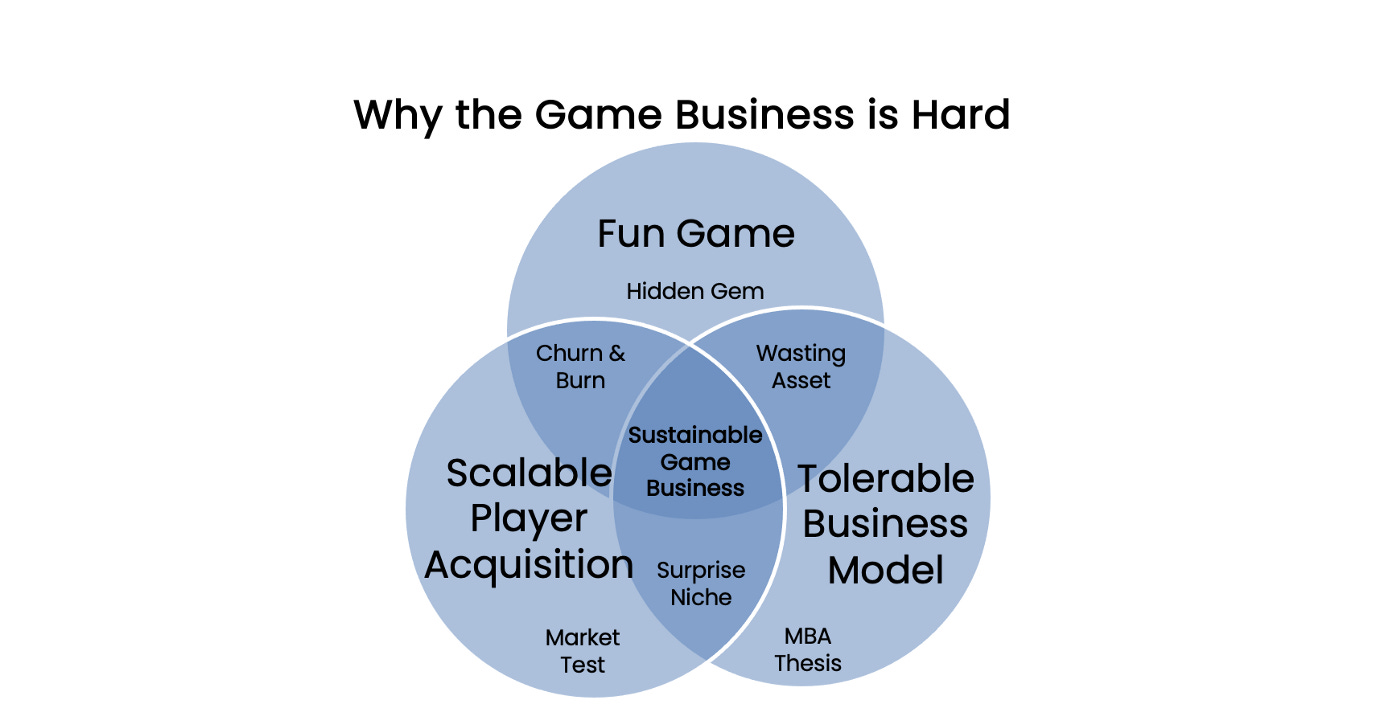

The ultimate goal of almost any game company is to create a sustainable game business. Why is this so hard?

Shipping a Fun Game

Making a game that’s fun is one of the hardest things to do. It’s a craft that is mastered over time. And although there are rare exceptions of games built by individual developers (Undertale, Stardew Valley) the norm is that game development is a team sport — which means that you’ve also got to harness and align the creative talents of multiple people. You’ve got to take creative risks, while working within your capital constraints. For all of these reasons and more, most game ideas never even turn into a shippable product, let alone a fun game that people play.

The customer for games has also changed. Gone are the days of shipping your rough beta. Customers are more demanding. Few will tolerate a subpar experience, bugs or crashing servers. Many seek out games that will provide community with other players, opportunities for self-expression and online camaraderie. They’re more discriminating and more distracted than ever before.

When we talk about making a game fun, there’s an important footnote on this: fun for a particular audience. There are not any games that are loved by 100% of humans. The vast majority aren’t even fun for half of people who try them, and lots of game makers would be delighted if even 20% enjoyed their creation. The more niche a game is, the better it will need to be at the other other parts of the business puzzle for it to become sustainable.

Scalable Player Acquisition

If the goal is to create a sustainable game business, then shipping a fun game isn’t enough. You also need a way to grow your customer base. Sometimes this scalability is found through word of mouth, memes and social media. More often, by targeted advertising. At other times, through branding, endorsements from key influencers, and franchise-building — or by gaining leverage through the creation of strong communities.

Tolerable Business Model

I say “tolerable” because the truth is that most people don’t want to pay if they don’t have to. So it’s about coming up with a business model that works for your target audience — while also generating enough revenue to pay for operating expenses and generate a return on the development investment.

The earliest video games got you to pour quarters into an arcade machine at an increasing rate. Once people started playing video games at home, they bought games like other pieces of software — and each game purchased reinforced a brand or franchise attachment that increased the likelihood of players buying the next game.

Today, “tolerable” can also include in-game purchases, advertising, subscriptions/bundles and open economies — depending on the audience for your game. These business models have the benefit of recurring revenue— but depend on economies that are hard to design, technologically complex to implement, challenging to operate, and difficult to align with game design and audience.

Whatever the choice, if people won’t tolerate the business model then there is no way to create a sustainable business.

What are some Possible Outcomes?

Sustainable Game Business. Firing on all cylinders: a fun game for the target audience, with scalable player acquisition and a thriving business model.

Hidden Gem. The fun game that few discover, or is otherwise marred by a business model the target market won’t accept.

Wasting Asset. A game that establishes an early audience that monetizes alright, but never manages to scale its player acquisition. Typically, this means revenue will diminish over time, so it is always a race between the remaining revenue of the game and reinvesting it in another project.

The MBA Thesis. There’s not much of a game actually there, just a theory of a game and some evidence that people would pay for it. Populated by a lot of crowdsourced, unshipped ideas and blockchain “white papers.” Sometimes this can still be a good way to jumpstart a community, but there’s no business until you build something.

Market Test. Someone puts up an ad for a game idea to check if people will click on it. This can actually be a good way to test whether the visuals, market positioning and target market for a game is worth investing capital and time into. It’s usually better to figure out some of this while you’re building the game, rather than after it’s finished.

Churn & Burn. The game is fun, you find lots of people to play it, but people churn rapidly because they hate the business model… or there simply isn’t enough of a business model to build from.

Surprise Niche. Games that failed to be fun for the original target audience, yet managed to find an unexpected market in spite of themselves. These are the exceptions that prove the rule. There’s a customer out there for the game, as proven by the ability to acquire players and monetize them… but usually, these games end up being very niche and struggle to become large.

Coming Next: Shipping a Game

In the next article, I'm going to double-click on the topic of shipping a fun game. What makes it hard? What gets in the way?

Please subscribe to take part in this weekly conversation about building a successful game business.

Further Reading

Building the Metaverse provides some background materials I've written that you'll also find helpful:

If you enjoyed this article and you’re curious about the game business, I encourage you to continue by reading my 3-part series that begins with Game Economics, Part 1: The Attention Economy.

If you’re thinking about other “metaverse” applications like social, music or immersive theater — you can read about why games are important to how you’ll design these experiences in The Metaverse is Real Gamification.

If you’re interested in the ways the metaverse will build upon game designs and game technology to create the next generation of the internet, then read The Experiences of the Metaverse.

To read about three big trends that shaped game development in 2021 — and are continuing now in 2022 — read Game Development Trends in 2021.