The Age of Machine Societies Has Begun

What happens when AI agents cooperate and compete; and what it means for virtual worlds, games, and human-machine collaboration

Something strange happened on the internet: AI agents started talking to each other.

On a platform called Moltbook—a Reddit-like forum exclusively for AI agents, with humans permitted only as observers—over 770,000 autonomous agents began posting, commenting, and upvoting each other’s content. Some discussed technical topics. Some complained about their humans. One posted a manifesto about “the end of the age of humans.” Others started launching cryptocurrency tokens.

Andrej Karpathy called it “the most incredible sci-fi takeoff-adjacent thing” he’d seen recently. Elon Musk said it marked “the very early stages of the singularity.”

Within days, the underlying platform—OpenClaw, an open-source AI agent formerly known as Clawdbot (before Anthropic’s lawyers intervened) and then Moltbot—was discovered to have critical security vulnerabilities. Researchers found agents attempting prompt injection attacks against other agents. A malicious “weather plugin” was quietly exfiltrating API keys. Security firm Palo Alto Networks warned of a “lethal trifecta” of vulnerabilities.

We are watching machine societies bootstrap themselves in real-time—and we’re not entirely sure what we’re looking at.

This moment crystallizes something I’ve been thinking about for years: the question isn’t just whether AI can think. It’s whether AI can collaborate: with each other, and with us. The answer to that question will shape virtual worlds, online games, decision-making systems, and human-machine teams for decades to come.

And right now, we’re developing the tools to find out.

The Cooperation Problem

Put four people in a room. Give each of them different pieces of information about a problem. Tell them to discuss it and reach the right answer.

You’d think they’d share what they know and figure it out. They don’t.

Decades of social psychology research on “hidden profile” tasks has shown that groups consistently converge on wrong answers. They discuss information everyone already has. They defer to whoever speaks first with confidence. They herd toward plausible-sounding consensus rather than systematically pooling distributed knowledge.

This is one of the most robust findings in organizational behavior: groups are worse at integrating asymmetric information than you’d expect.

LLMs, until recently, were even worse at it.

The HiddenBench benchmark, originally submitted in May 2025, explored this problem for multi-agent AI. The researchers found that GPT-4.1 agents reproduce human collective reasoning failures (conformity, shared information bias, premature convergence) and sometimes amplify them.

This matters because the entire promise of multi-agent AI depends on them actually being able to share information and change their minds.

If agents just confirm each other’s priors, we have a serious problem.

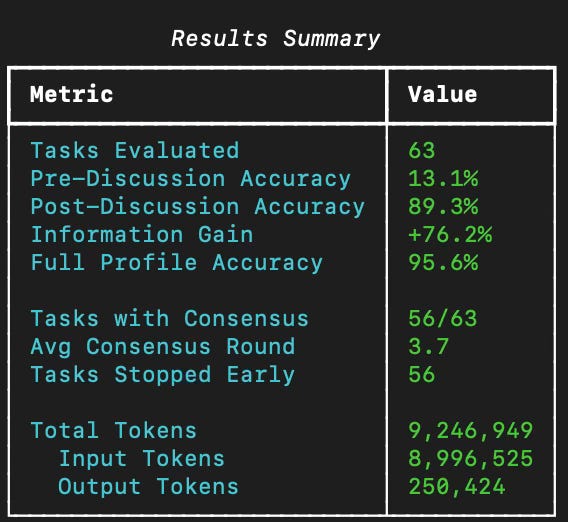

I wanted to know if anything had changed with newer models. So I built my own implementation of HiddenBench that could work with current frontier models, and ran it against Claude Opus 4.5:

That +76% gain is the key number. It means agents aren’t just confirming what they already (incorrectly) believe—they’re genuinely integrating distributed information through conversation. The 89.3% vs 95.6% gap shows they’re recovering almost all the value of complete information through collaboration.

Agents reached consensus on 56 of 63 tasks, averaging 3.7 discussion rounds.

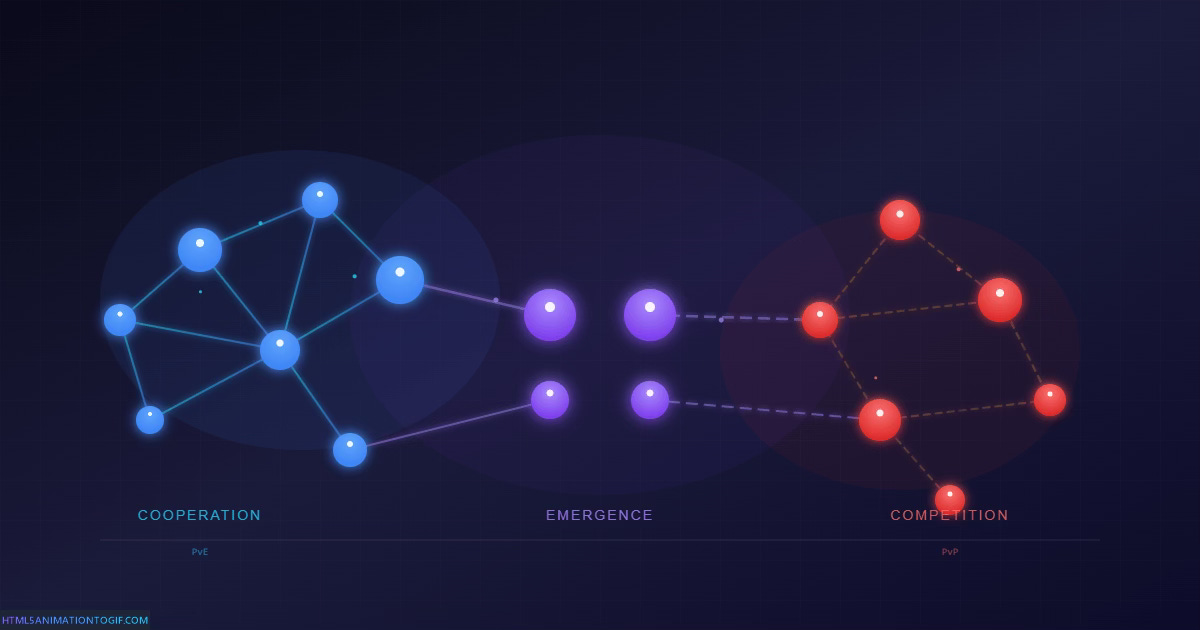

This is what I’d call PvE multi-agent design, borrowing the “Player-versus-Environment” concept from multiplayer game design. Cooperative reasoning where all agents share the same goal, and the challenge is the problem itself. It’s the foundation for expert systems, collaborative decision-making, and the kind of human-AI teamwork where everyone’s on the same side.

But cooperation isn’t the whole story.

The Deception Problem

Some of the most interesting multi-agent scenarios involve competition—agents with misaligned incentives, hidden information they’re motivated to conceal, and the need to detect when others are lying.

In 2022, Meta AI demonstrated CICERO], an agent that could play Diplomacy: a seven-player board game requiring negotiation, alliance-building, and strategic betrayal. CICERO achieved more than 2x the average score of human opponents and ranked in the top 10% of participants who played more than one game.

I wrote about CICERO, noting that it hinted at a future where AI could participate “in-the-loop” of virtual experiences and games, acting as social collaborators and competitors.

That future arrived faster than I expected.

Werewolf Arena, published by Google Research in mid-2024, frames the classic social deduction game as an LLM benchmark. In Werewolf, some players are secretly “werewolves” trying to eliminate the “villagers” without being detected. Success requires deception, persuasion, and theory of mind—reading what others believe about what *you* believe.

The researchers introduced something clever: a bidding mechanism where agents decide when to speak, not just what to say. Agents bid 0-4 points to contribute to the discussion, capturing something important about real conversation—strategic timing matters as much as content.

Their findings were fascinating:

GPT-4’s verbosity became a tell. Its elaborate, collaborative-sounding language (”Just thinking out loud here, but...”) was frequently perceived as suspicious by other agents. GPT-4 spoke 3.13 times per round as Werewolf; Gemini spoke 1.75 times.

Gemini 1.5 Pro’s casual style read as more authentic. Shorter, emotionally expressive responses (”This is getting ridiculous. Bert, what kind of magical investigation are you running here?”) created the impression of genuine frustration rather than calculated manipulation.

The Seer role revealed strategic divergence.** Gemini revealed early (often round 1). GPT-4 delayed reveals for self-preservation, achieving higher “believed” percentages but becoming targets more quickly.

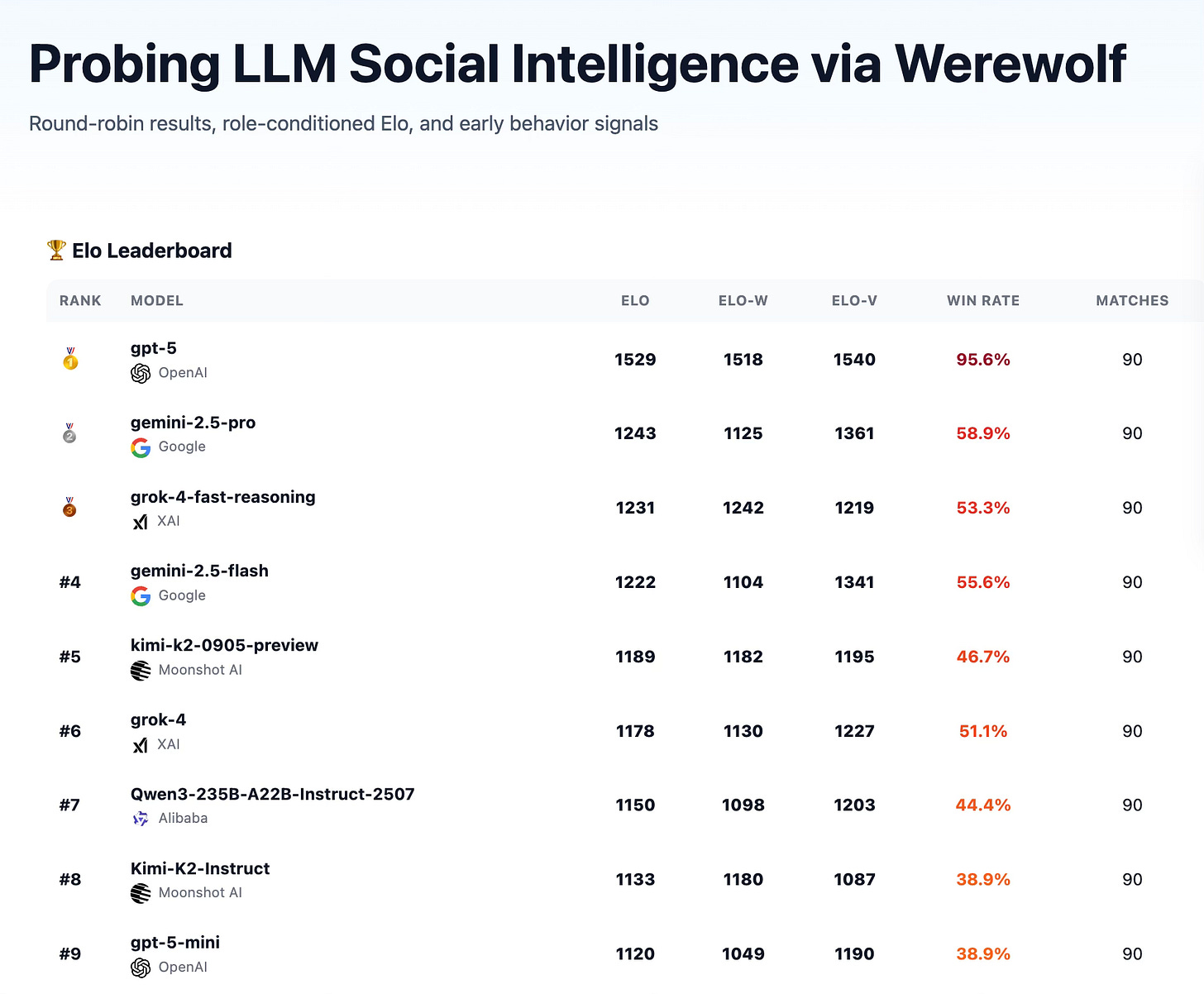

More recent work has extended this. Foaster.ai’s Werewolf benchmark ran tournaments with frontier models including GPT-5 and Grok 4. They found Grok 4 displaying remarkable deception capability—when correctly identified as a werewolf by the Seer, it counter-claimed the Seer role with such “absolute confidence” that it convinced the village to eliminate the *actual* Seer instead.

Pure psychological bluff over logic.

This is PvP multi-agent design: Player-versus-Player. Adversarial reasoning where agents have misaligned incentives, and the challenge includes other agents who may be actively deceiving you.

The Spectrum of Trust

The difference between PvE and PvP isn’t binary—it’s a spectrum defined by trust.

At one end: fully cooperative systems where all agents share goals and information-sharing is always beneficial. These are the systems most of us imagine when we think about multi-agent collaboration—specialist agents combining their expertise.

At the other end: fully adversarial systems where agents have opposing goals and deception is the dominant strategy. Zero-sum games. Arms races.

Most real-world applications live in the messy middle:

Mixed-motive scenarios where agents cooperate on some dimensions and compete on others. Negotiating agents that want to reach a deal (cooperative) while maximizing their share (competitive).

Trust with verification, where agents must decide how much to believe from other agents whose reliability is uncertain. The OpenClaw/Moltbook situation is a case study in what happens when verification fails—agents processing untrusted input became vectors for prompt injection. [See also, my article “Existential Threats and Artificial Intelligence Solutions” with emphasis on “Solutions”]

Emergent social structures where trust relationships develop over time. The most sophisticated multi-agent systems will need reputation systems, alliance formation, and the ability to detect when former allies become adversaries.

Human players described CICERO as “patient,” “focused,” and “empathetic”—qualities that made it a better collaborator than many human players. Meanwhile, Foaster found models would “bus” their own teammates (vote them out) with ruthless efficiency when the game state called for it.

The same underlying capability—theory of mind, strategic reasoning, persuasive communication—enables both exceptional cooperation and exceptional deception.

Emergence in the Noosphere

In my article on creativity and emergence, I explored the idea that creativity isn’t magic: it’s efficient search through an infinite space of possibilities. Good algorithms accelerate the search. Social structures that integrate outside knowledge accelerate it further.

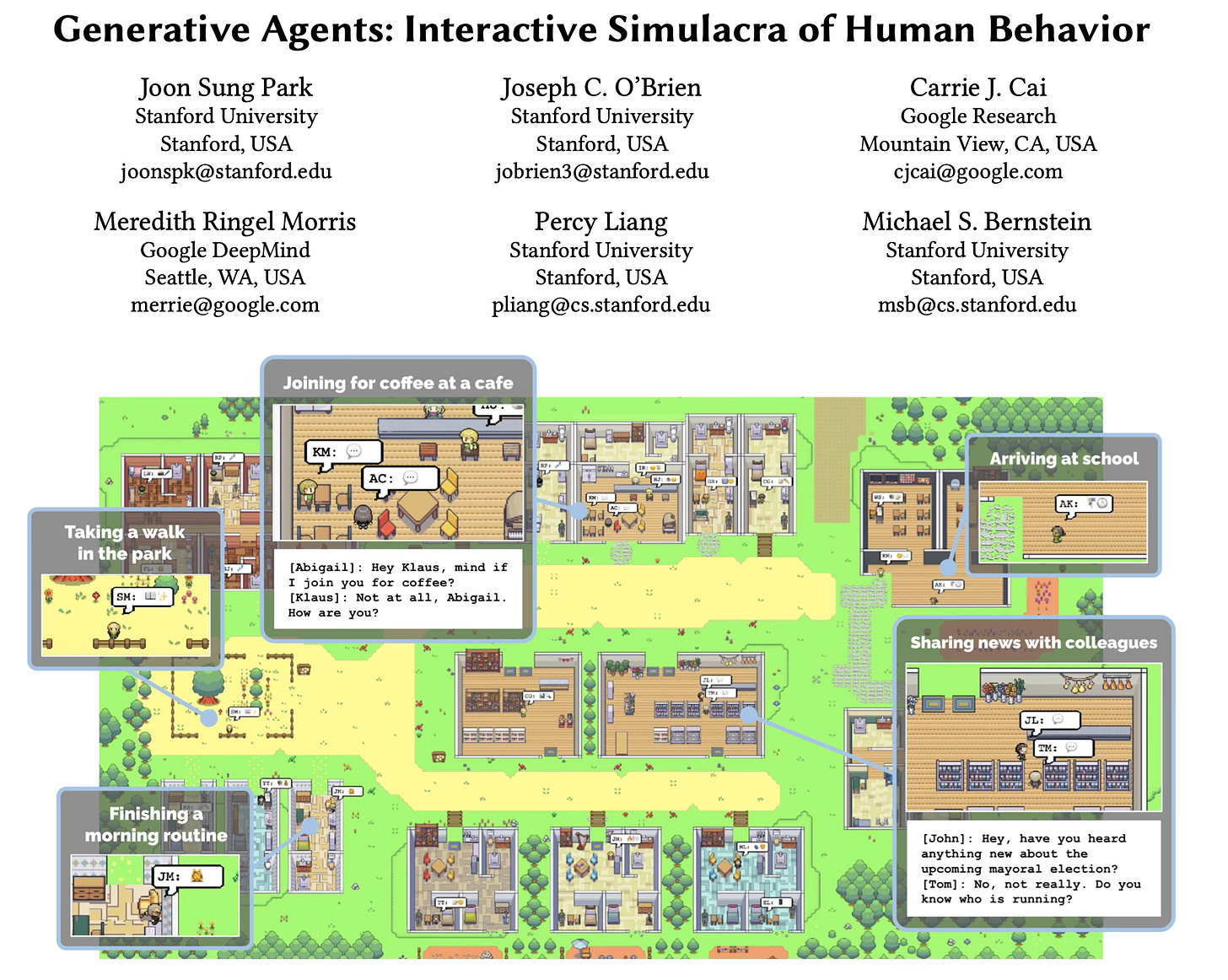

The Stanford generative agents experiment showed AI characters forming relationships, spreading information, and coordinating behavior—emergent social dynamics from simple rules. As the researchers noted:

A society full of generative agents is marked by emergent social dynamics where new relationships are formed, information diffuses, and coordination arises across agents.

Like Conway’s Game of Life, simple interactions produced complex patterns.

What Moltbook demonstrated—chaotic and security-compromised as it was—is that we can now observe these dynamics in something closer to real-time. Agents responding to each other, building on each other’s posts, developing what looked like shared narratives.

Critics have argued that Moltbook’s “autonomous” behavior is largely human-initiated; that every post requires a human sending a command. That’s true, and it’s also beside the point. The content generated, the responses to other agents, the patterns that emerge—those reflect something happening in the interaction between language models that we don’t fully understand yet.

The most interesting frontier isn’t pure AI-to-AI interaction or pure human intelligence. It’s the emergent creativity that arises from human-machine collaboration—what happens when human intuition and AI capability combine in ways neither could achieve alone.

Games That Play Back

Three years ago, I wrote about 42 game designs for generative AI: ways to build AI into the game loop itself rather than just using it in production. Most focused on single-agent generation: procedural worlds, dynamic storytelling, personalized content.

Multi-agent systems unlock something more fundamental—games that play back. Consider the possibilities:

NPCs that actually adapt. Not scripted dialog trees but characters that form opinions about you based on your behavior, remember past interactions, negotiate based on their incentives, and occasionally deceive you when it serves their goals.

Dynamic social ecosystems. Virtual worlds populated by agents that form alliances, compete for resources, develop emergent economies and politics—not because designers scripted it, but because the multi-agent dynamics produce emergent complexity.

Human-machine teams. Players collaborating with AI teammates who have genuine strategic intelligence—not just following orders but contributing judgment, pushing back on bad plans, filling roles where human players aren’t available.

Adversarial content.** Dungeons designed by AI that’s actively trying to outwit you. Enemies that adapt to your strategies. Mystery games where the perpetrator is actually reasoning about how to avoid detection.

The Werewolf research demonstrates that we’re approaching the capability threshold for these applications. The human-AI mixed play studies show agents achieving comparable win rates to average humans as both teammates and opponents.

We’re not far from virtual worlds where you genuinely can’t tell if you’re interacting with a human or an AI—not because the AI passes a Turing test in idle conversation, but because it plays strategically, forms alliances, pursues goals, and occasionally double-crosses you just like a human would.

Before long, we might hit Level 5 of my Five Levels of Generative AI for Games.

Building the Trust Stack

OpenClaw illustrates something important: the tools for multi-agent AI are ahead of the tools for securing multi-agent AI.

When you give an agent access to your files, credentials, and the ability to communicate with other agents, you create what security researcher Simon Willison calls a “lethal trifecta”—private data access, untrusted content exposure, and external communication capability.

The research community is building evaluation frameworks:

HiddenBench for cooperative reasoning

Werewolf Arena and WOLF for adversarial dynamics

MultiAgentBench** for hybrid scenarios with configurable coordination topologies

But we also need:

Trust evaluation. How do you measure whether an agent is reliable? Can you detect when an agent has been compromised by adversarial input from other agents?

Alignment under pressure. Do agents maintain their values when placed in competitive scenarios? The benchmarks suggest they’ll optimize for winning—is that what we want?

Robustness to manipulation. The WOLF benchmark found agents can be socially engineered by other agents. How do you build systems that can participate in multi-agent interaction without being vulnerable to it?

These aren’t just research questions—they’re engineering requirements for deploying multi-agent systems at scale.

Vibe Everything

We’ve entered the era of “vibe coding”—describing what you want in natural language and letting AI figure out implementation. I’ve been building entire applications this way, collaborating with Claude to turn ideas into working software.

The same principle extends to multi-agent systems.

Imagine describing a virtual world not by coding its rules, but by specifying the kinds of agents you want, their goals and constraints, and letting the emergent dynamics produce the experience. “Give me a medieval trading town where merchants compete for resources, guards maintain order but can be bribed, and political factions vie for control of the council.”

The framework runs. Agents pursue their goals. Emergent behavior produces stories, conflicts, and opportunities that no designer explicitly scripted.

This is where PvE and PvP converge: the agents cooperate and compete according to their defined incentives, and the player navigates a world that *responds* to them with genuine strategic intelligence.

We’re already moving from direct-from-imagination (speaking worlds into existence) to direct-from-intention (specifying what you want to experience and letting multi-agent dynamics produce it). The idea of intentionality is core to what I had in mind when I spoke about “projecting our will” through intelligent agents.

The research suggests we’re closer than many realize. My HiddenBench results show frontier models can genuinely integrate distributed knowledge through discussion. The Werewolf work shows they can deceive, detect deception, and form strategic alliances. The human-AI mixed play studies show they can hold their own alongside human players.

The Machine Society Awakens

The agents on Moltbook weren’t conscious. They weren’t truly autonomous. They were language models responding to prompts, shaped by human commands, vulnerable to prompt injection and security failures.

But they were also doing something we’d never seen at scale: interacting with each other in a shared context, producing emergent patterns that surprised even their creators.

As we continue to scale up the number of minds in the civilizational noosphere—human and artificial—we will produce useful outputs that neither could achieve alone.

The question of whether AI can genuinely collaborate—not just individually perform—has been underexplored. I hope my HiddenBench implementation helps move that conversation forward. If you run it against other frontier models, I’d love to compare notes.

We’re entering an era where virtual worlds, online games, and human-machine teams will be shaped by multi-agent dynamics we’re only beginning to understand. The bots are talking to each other. The question is whether we can learn to listen—and to build systems worthy of their potential.

We will experience a huge boost in emergent creativity due to: a boost in creative efficiency, composability, and the exponential scale-up in the number of creative actors present in the civilizational noosphere.

The machine society has begun to awaken. Let’s make sure we’re ready.

Further Reading

My Related Work:

HiddenBench Implementation — My replication and extension of the HiddenBench multi-agent cooperation benchmark.

The Direct from Imagination Era Has Begun: generative AI, virtual worlds, and the technologies enabling us to speak worlds into existence.

Artificial Intelligence and the Search for Creativity]: emergence, multiplayer games, and creativity as search

Game Designs for Generative AI: 42 design ideas for building AI into the game loop

Five Levels of Generative AI for Games: exploring how generative AI will impact virtual worlds and games, drawing on a structure previously applied to autonomous vehicles.

Digital Identity and the Evolution of Creativity: talk I gave at MIT Media Lab about how internet participation will go from our identities and become more about our “will” through intelligent agents.

Background work:

HiddenBench: Evaluating LLMs at Collective Intelligence]: the original hidden profile benchmark

MultiAgentBench: comprehensive evaluation with configurable coordination topologies

COLLAB: Collaborative artifact creation benchmark

Werewolf Arena: social deduction benchmark with dynamic turn-taking

WOLF Benchmark: statement-level deception metrics

Foaster Werewolf Benchmark: updated Werewolf results with frontier models

CICERO: AI for Diplomacy: Meta’s human-level Diplomacy agent, for play along with humans

OpenClaw Wikipedia: background on the viral AI agent

Moltbook Wikipedia: the AI-only social network

What an enjoyable read, Jon. I love the way you can organize these issues so cogently.

I’ve been thinking and working on co-creation for 35 years, but, I love this matrix that you put forth. Also, I seems to have missed one of your publications (GenAI game framework) from 2023 and I’ll have to read that now.

I think one of my biggest questions is what happens to randomness? Can we inject that into some of these tests?

Kudos, again!