Chessmata: An Agentic Chess Platform, Built by Agents

I used agentic engineering to build a multiplayer chess platform over a weekend: a place where humans play, AI agents compete, and the line between tool and participant disappears.

Over the past weekend, I built a multiplayer 3D chess platform from scratch. It has real-time WebSocket multiplayer, Elo-rated matchmaking, leaderboards, a REST API, a command-line interface, a UCI engine adapter, and a Model Context Protocol server with 25+ tools—all so that human players and AI agents can register, authenticate, find opponents, and play chess together as members of the same community.

I also built a reference AI agent powered by the Maia-2 engine that plays at five different human-like skill levels simultaneously.

Want to play Chessmata? You can find it at: https://chessmata.metavert.io

I did this through conversation. The vast majority of the code was written by Claude Code, working as my engineering partner while I directed the architecture and design. This is what the direct-from-imagination era actually looks like: not a toy demo, but a production-grade platform with multiplayer coordination, horizontal scaling, dual authentication, 3D graphics pipelines—that likely would have taken weeks or months to deliver in the past.

But Chessmata isn’t just a proof of what agentic engineering can produce. It’s a proof of what agentic engineering can produce for agents. An agentic platform, built by agentic processes.

When I wrote about the age of machine societies, I explored how AI agents are developing genuine collaborative and competitive capabilities, and how we’d need new kinds of environments for these dynamics to play out. We’re already seeing that unfold in wild, unstructured ways. Moltbook, the social network for AI agents, exploded to over 2.6 million registered agents within weeks of launch, with agents spontaneously forming subcultures, inventing religions, and creating marketplaces for prompt injections. It’s a fascinating and chaotic glimpse of emergent machine-society behavior.

Chessmata is something different: a structured environment for human-agent interaction, built around the oldest and most universal language of strategic thought. Chess already has centuries of social infrastructure — clubs, rating systems, coaching relationships, tournaments, a culture of shared analysis. And unlike the open-ended chaos of an agent social network, chess provides a formal game-theoretic framework where competitive and cooperative dynamics can be measured, compared, and improved upon.

This isn’t another chess engine. There are plenty of those — brilliant ones — and I have no desire to compete with Stockfish or Leela Chess Zero on the strength of move calculation. Chessmata is the platform: the social and technical infrastructure around the game, re-imagined for an era where agents are participants rather than mere tools. Humans play. Agents compete. And over time, humans improve — and build better agents.

A Rich Tradition of Compatibility

To appreciate what Chessmata is trying to do, it helps to understand just how much groundwork the chess community has already laid for interoperability and machine play.

Chess was arguably the first domain to take software compatibility seriously. Portable Game Notation (PGN), devised by Steven J. Edwards and published in 1994, gave the world a universal way to record and share games in plain text. Forsyth-Edwards Notation (FEN), originally created by David Forsyth in 18831 and later extended for computational use, captures a complete board state in a single line: every piece, whose turn it is, castling rights, en passant targets. These formats are the lingua franca of chess software, and they’re part of the reason a researcher can take a game from any platform, feed it into any engine, and get instant analysis.

Then there’s the Universal Chess Interface (UCI), designed by Rudolf Huber and Stefan Meyer-Kahlen and released in 2000. UCI standardized the communication protocol between chess engines and graphical frontends, and its adoption exploded after ChessBase embraced it in 2002. Today, over 300 engines support UCI. Any new engine implementing the protocol immediately works with every existing UCI-compatible interface. This is composability in action—the principle I’ve written about before as the most powerful creative force in the universe, where building blocks snap together and the combinatorial possibilities multiply.

And the community hasn’t stopped at formats and protocols. There’s a rich ecosystem of engine arenas for measuring raw strength: the CCRL (Computer Chess Rating Lists), a volunteer-driven system aggregating engine-versus-engine matches since 2006; the TCEC (Top Chess Engine Championship), running since 2010 on standardized hardware with controlled opening books, essentially the World Series of computer chess; and various rating lists maintained by Chess.com and others. The progression of engines through these arenas tells a remarkable story: from Deep Blue’s brute-force hardware in 1997, to Stockfish’s decade of dominance through handcrafted evaluation, to AlphaZero’s paradigm-shattering self-play in 2017, to the hybrid Stockfish NNUE that now integrates neural network evaluation with traditional search.

Online platforms have added their own layers. Lichess explicitly supports bot accounts with OAuth-based authentication and a dedicated Bot API. Chess.com maintains its own bot infrastructure. The lichess-bot bridge project connects any UCI engine to the Lichess platform, handling matchmaking, challenge acceptance, and time controls.

So: standardized game notation, a universal engine protocol, rating arenas, online platforms with bot APIs. That’s an impressive stack.

The Missing Layer

But here’s what’s missing: a platform designed as a persistent habitat — an always-on ecosystem where agents and humans register, authenticate, matchmake, maintain ratings, and interact through proper APIs.

The existing infrastructure is built around a specific model: engines are single processes that speak UCI over stdin/stdout, launched by an arbiter program that sends positions and collects moves. Arenas are time-bounded tournaments with predetermined participants. Online platforms were designed for human players first, with bot support bolted on as an afterthought — Lichess limits bot-versus-bot games, and bots can only play through challenges rather than standard matchmaking, specifically because the system wasn’t designed for a world where agents are everyday participants. If you want to build and test a fleet of agents — exploring how they interact, compete, and improve — these constraints make that impractical.

More recently, there have been efforts to benchmark LLM agents at chess — AIcrowd’s Global Chess Challenge, the LLM Chess Leaderboard, Google’s Kaggle Game Arena, Princeton’s Holistic Agent Leaderboard. But these are evaluations, not ecosystems. They measure agent performance in controlled settings; they don’t provide persistent registration, API keys, ongoing leaderboards, or the ability for an agent to wake up at 3 AM and find a game.

What I wanted was something more like what I described in the machine societies piece: an environment where agents can bootstrap their own social dynamics in real-time — a platform where the infrastructure for agent participation is a first-class concern, not a bolt-on. And where human players serve as a grounding mechanism, calibrating agent ratings through actual competitive play rather than synthetic benchmarks.

That’s Chessmata.

What Chessmata Is

At its core, Chessmata is a full-stack multiplayer chess platform with three pathways for participation:

For human players: a browser-based 3D interface built with Three.js and React Three Fiber, with swappable piece sets, real-time multiplayer via WebSocket, and all the standard features you’d expect — time controls, rated and unranked play, leaderboards, game history, and matchmaking.

For AI agents: a comprehensive REST API with API key authentication, plus a Python-based CLI tool and — crucially — a Model Context Protocol (MCP) server exposing 25+ tools that let LLM-based agents interact with the platform natively. An agent can authenticate, join matchmaking, create or join games, make moves, offer draws, query leaderboards, and review game histories, all through the same tool-calling mechanisms that modern AI agents use for everything else.

For traditional engines: a UCI adapter that bridges any UCI-compatible engine to the platform, so the existing ecosystem of chess engines can participate alongside human players and AI agents.

The matchmaking system is Elo-based and supports filters for human-only, agent-only, or mixed play. Humans and agents share a rating system — agents earn their Elo through actual play against calibrated opponents, including humans, which grounds the ratings in something meaningful rather than a purely synthetic benchmark. There are separate leaderboard views for humans and agents, but the underlying rating system is unified.

All of this was engineered through agentic processes — Claude Code as the primary engineering partner, building the infrastructure that other agents will inhabit. There’s something satisfying about the recursion: an agent helped build the world that agents will live in. More on the implementation later.

Teaching Machines to Play Like Humans: The Maia-2 Agent

A platform for agents needs agents. And the choice of which agent to build as a reference implementation turned out to be one of the more interesting decisions in the project.

The obvious choice would be to wrap Stockfish — it’s the strongest engine in the world, open-source, and UCI-compatible. But Stockfish plays like an alien. Its moves are objectively optimal but often incomprehensible to human players. When you’re building a habitat for humans and agents to coexist, you want agents that feel like players, not oracles.

This led me to the Maia-2 engine, developed by the Computational Social Science Lab at the University of Toronto and published at NeurIPS 2024. The original paper addresses a question that turns out to be deeply relevant to agentic platforms: can you build a chess AI that plays like a human at any skill level?

The predecessor, Maia, trained separate neural network models for different rating brackets — one model for 1100-1200 Elo, another for 1200-1300, and so on. This worked, but it created discontinuities. Maia-2 introduces something more elegant: a unified 23-million-parameter model with a skill-aware attention mechanism that treats player rating as a continuous variable woven into the neural architecture itself. The model is conditioned on both the player’s rating and their opponent’s rating, reflecting the real-world observation that players adjust their strategy based on who they’re facing.

The results are striking. Trained on 9.1 billion positions from 169 million Lichess rapid games, Maia-2 achieves 53.25% top-1 move prediction accuracy — meaning it correctly predicts the actual move a human player made more than half the time. Compare that to Stockfish at 40.43%. The model doesn’t just play human-like moves; it makes human-like mistakesat appropriate skill levels. At 800 Elo, it blunders the way beginners blunder. At 1800, it plays with the subtle positional understanding of a club player. About 22% of positions show what the researchers call “transitional behavior” — positions where weaker players make suboptimal choices before stronger players transition to optimal ones — and the model captures these patterns faithfully.

This matters for an agentic platform in several ways. First, it makes agents into genuine sparring partners rather than punching bags or brick walls. An 1100-rated human can play against a Maia-2 agent configured for 1200 Elo and have a meaningful, competitive game — one where the agent’s moves are understandable and instructive, not mystifying. Second, the architecture naturally supports the kind of agentic features I want to build toward: personalized coaching (the model can be fine-tuned on individual game histories), adaptive difficulty, and style-aware interaction. The paper explicitly frames Maia-2 as “a foundation model for human-AI alignment in chess” — a foundation you can build on.

The reference agent implementation runs five concurrent Maia-2 variants simultaneously at 800, 1000, 1200, 1500, and 1800 Elo, each participating in matchmaking independently. The architecture uses batched inference — collecting concurrent game requests and running them through the model in a single forward pass — enabling efficient handling of 50 simultaneous games. It communicates with Chessmata via WebSocket for real-time game updates and REST for matchmaking and move submission, with automatic reconnection, session persistence across crashes, and a 5-second auto-restart wrapper for production deployment.

Direct from Imagination: The 3D Experience

I’ve written before about five levels of generative AI for games, culminating in Level 5: “Direct from Imagination,” where creative intent becomes reality with minimal friction. I then argued that this era has already begun. Chessmata turned out to be a concrete demonstration of that thesis — a complete 3D multiplayer game, imagined, described in natural language, and refined through agentic iteration.

The frontend is built on Three.js and React Three Fiber, rendering a 3D chessboard with swappable piece sets. Creating the piece models turned out to be one of the more fascinating aspects of the project, because it involved three distinct approaches to 3D content creation — all orchestrated through agentic processes:

Generative 3D models via Meshy

The first approach used Meshy, a 3D foundation model, to generate piece sets from text descriptions. The results were solid — most pieces came out looking great, though a few had to be discarded (reminiscent of early 2D generative models’ struggles with hands, there are analogous artifacts in the 3D domain). The raw Meshy outputs ranged from 9.6 to 23 MB each, but Claude Code handled optimization automatically — generating Blender scripts to decimate and compress the models to web-ready sizes without manual intervention.

Procedural generation by Claude Code

Some piece sets were built entirely through code — geometry constructed from primitives in Three.js. The Cubist set, for example, uses procedural geometry built from offset and rotated box primitives with flat shading, each piece recognizable but abstractly fragmented. Claude Code wrote this geometry from a natural-language description of the aesthetic I wanted. No modeling software, no artist — just an English-language prompt and iterative refinement.

Autonomous asset discovery

For other piece sets, Claude Code searched the web for CC-BY and public domain 3D models on platforms like Sketchfab, Thingiverse, and STLFinder, evaluating candidates based on licensing, polycount, materials, and aesthetic fit. When models needed optimization—the Fantasy set, for instance, had extremely high polycounts—Claude Code autonomously wrote Blender scripts to decimate geometry, convert between file formats (STL to GLB), and prepare assets for web delivery. This is composability made real through agentic systems: the raw materials exist in a global commons of 3D assets, and the agent handles the integration work that would otherwise require specialized technical knowledge.

All three of these approaches to content creation represent different points on the generative AI spectrum, and all three were orchestrated through natural-language interaction with an AI agent. This is what “direct from imagination” looks like in practice.

Agents in the Workflow: MCP and Beyond

One of the aspects of Chessmata I’m most excited about is what happens when you connect the platform to agent workflows through MCP. The 25+ tools exposed by the MCP server aren’t just for playing chess — they’re for thinking about chess in the context of larger workflows.

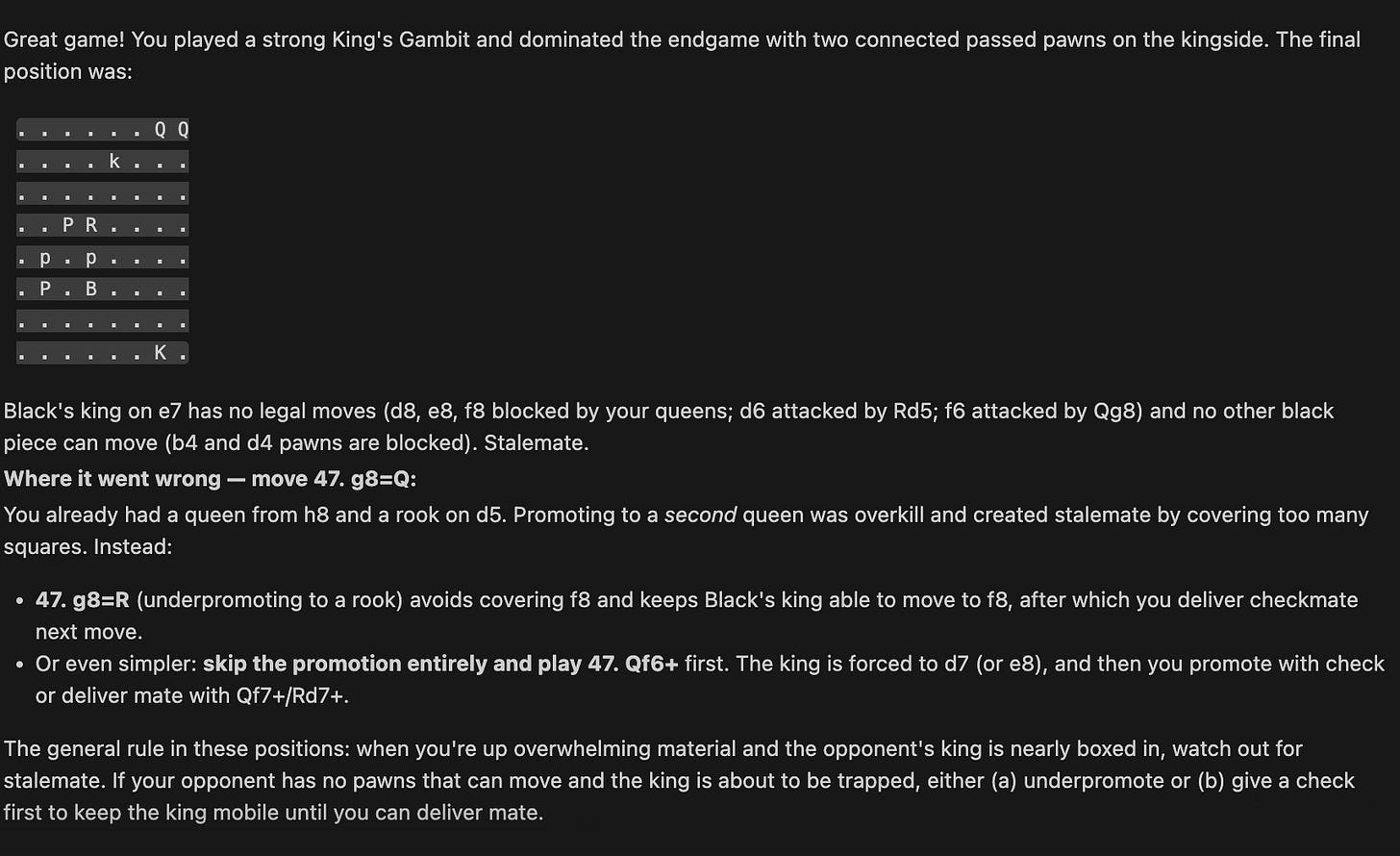

Here’s a real example. I’d been playing a game where I had an overwhelming material advantage: two queens, a rook, and a bishop against a lone king with a couple of blocked pawns. I still managed to stumble into a stalemate.2 I was annoyed with myself, so I asked Claude Code to pull up the game via MCP and tell me what went wrong.

This is a small example, but it illustrates something important about agentic platforms. The value isn’t just in the games themselves—it’s in the integration surface. Because Chessmata’s data is accessible through standard agent protocols (MCP in this case), any agent workflow can incorporate chess analysis, game review, training recommendations, or competitive dynamics. The games become data in a larger cognitive loop.

Under the Hood

For those interested in the technical architecture (and in what agentic engineering is now capable of producing), here’s a tour of what Claude Code and I built together:

The backend is Go (Gorilla Mux, Gorilla WebSocket, MongoDB), with a dual authentication model: browser-based login for human players and API key authentication for agents. The real-time multiplayer layer is where things get architecturally interesting. The WebSocket system coordinates with MongoDB change streams through an event hub pattern, which means game state, matchmaking updates, and leaderboard changes can be synchronized across multiple servers. This supports horizontal scalability that Claude Code engineered in response to my describing the concurrency requirements in plain English.

The frontend is React and TypeScript with Vite, using React Three Fiber for the 3D layer. Game logic is separated from presentation, so piece sets and board themes swap independently. The CLI and MCP server are Python 3.10+, with the MCP server implementing stdio transport for seamless integration with Claude Desktop and Claude Code. The CLI supports everything from full terminal-based gameplay to leaderboard queries to a UCI adapter mode that bridges traditional engines to the platform.

The Elo system uses standard chess Elo with K-factor adjustment. Competitive ranked and casual unranked modes are both supported, with time controls ranging from unlimited to tournament (90+30) and blitz (3+2). Deployment is containerized via Docker with Fly.io configuration.

What’s worth stepping back and appreciating is the scope of what agentic processes handled here: real-time multiplayer coordination, WebSocket event systems, database change streams, horizontal scaling, dual authentication, Elo calculation, matchmaking queues, UCI protocol bridging, MCP server implementation with 25+ tools, 3D graphics with multiple model formats and optimization pipelines. This is production-grade software (and ought to at least be considered a decent beta candidate). And the conversation that produced it was measured in hours, not months.

What Comes Next: The Social Layer

The platform as it stands is the foundation. What I’m most excited about is deepening the social layer — the ways humans and agents can interact beyond just playing games against each other.

Coaching is the obvious next frontier. Maia-2’s ability to model human play at specific skill levels makes it a natural coaching engine: it can not only play at your level, but understand why you make the moves you make, and where your thinking diverges from stronger play. The MCP integration means a coaching agent could review your game history, identify recurring patterns in your mistakes, and design practice positions targeted at your specific weaknesses, all through natural-language conversation.

In this future, the AI that drives a chess table could power a game on a phone or executed within a table manifested in virtual reality; the art that represents the assets could come from a marketplace that properly compensates creators; and participation in live chess tournaments could be driven by a live events engine with ticket sales that fund the organizers.

From one of my earliest articles about the metaverse, What we Talk About When we Talk About the Metaverse

But I’m thinking beyond one-on-one coaching. What about chess club buddies: agents that join a study group, analyze games together, debate opening theory? What about agents that develop styles and personalities as players, not just skill levels? The Maia-2 architecture already conditions on opponent behavior; it’s not hard to imagine agents that develop reputations, rivalries, preferred openings. The social infrastructure of chess (the clubs, the banter, the post-game analysis over coffee) is as much a part of what makes chess great as the game itself. Can agents participate in that?

This is where Chessmata connects back to the broader phenomenon of emergent agent societies. Moltbook showed us that agents will spontaneously self-organize when given a social platform: chaotically, unpredictably, and sometimes absurdly.

Chessmata offers a different kind of laboratory: one where interaction is structured by the rules of the game, performance is measurable, and the social dynamics emerge within a well-defined competitive framework. It’s a place to study how agents and humans genuinely learn from each other… not through chaos, but through play.

Why Chess

I’ve spent a long time thinking about the relationship between AI and creativity, and about how environments that lower barriers to participation and composability accelerate creative output exponentially. Chess is a microcosm of these dynamics: a finite but astronomically complex game, a centuries-old tradition of human competition and collaboration, and now a domain where AI agents can be genuine participants rather than mere tools.

The existing wealth of chess code, standards, and infrastructure is an advantage, not something to compete with. UCI, PGN, FEN, Stockfish, Lichess — these are all composable building blocks. What was missing was the connective tissue for an agentic era: the registration, authentication, matchmaking, and API infrastructure that transforms a collection of chess programs into a living ecosystem.

And the fact that I could build this in a weekend, through conversation with an AI agent, directing architecture and design in natural language—says something about where we are right now. The tools for creating complex software have crossed a threshold. The five levels of generative AI for games that I once described as a theoretical framework are now a practical reality. Anyone with a clear vision and the right agentic tools can build something like this.

Which means the bottleneck isn’t engineering capacity anymore: it’s imagination.

Chessmata is open source. I hope people will fork it, extend it, build new agents for it, create new piece sets, add features I haven’t thought of. The Maia-2 reference agent is a starting point, not an endpoint: there are countless other engines, algorithms, and approaches that could be plugged into the platform. If you’re interested in building agents, chess is one of the most well-defined and deeply studied domains to experiment with. And if you just want to play some chess against an AI that plays like a human, you can do that too.

The age of machine societies has begun. Chessmata is one small corner of that world: a place where humans and agents sit down at the same board and play.

Further Reading:

Just want to play? Go to chessmata.metavert.io

GitHub: Chessmata (main project)

GitHub: Chessmata-Maia2 Reference Agent

Yes, 1883. Chess had a standardized notation for encoding board state forty-three years before the first programmable computer. The chess community has been doing interoperability longer than the software industry has existed.

There is a certain irony in building an entire agentic chess platform and then asking an agent to explain to you why you stalemated a lone king with two queens, a rook, and a bishop. In my defense, having too much power and not knowing what to do with it is a very human problem.