Spatial Computing Won't Disrupt Games

But games will transform almost everything else

Here is what I discuss in this article:

What it means to disrupt an industry; why spatial probably won’t do it to games

Why games aren’t the “killer app” for spatial computing—nor do they need to be

Some amazing game experiences that make use of the uniqueness of spatial computing

How spatial computing applications are learning from games

And how games are changing everything else

Disruptive Innovation

In my article on game development trends in 2024, I explained:

For something to be “disruptive,” it means expanding the size of a market by making a previously-scarce product or service available to a much larger audience, typically by a business model that dramatically lowers cost or a technological transformation that makes the market far more accessible, replacing incumbents in the process. The last truly disruptive technology in video games was free-to-play mobile, which added billions of players. Today, half the industry’s revenue is generated by mobile.

“Disruption” is one of the most abused terms in the technology industry, and people tend to use it to mean “much better than the previous version.” Clayton Christensen, who coined the term “disruptive innovation” would call things that are simply better a “sustaining innovation.”

With a disruptive innovation, entire industries can be rendered obsolete. Entirely new classes of customers emerge in quantities nobody has seen before. And established partnerships, suppliers and distribution channels may no longer matter.

However, it’s important to note that disruption doesn’t always mean decline. This seems especially true with media industries, where new forms of media consumption seem to be additive. We probably won’t stop watching movies because we have computer games and spatial media—and even when we tend to find a new way to deliver games1 (such as mobile) the other forms frequently keep moving forward.

What Might Spatial Computing Disrupt?

Fixed-location physical screens. You don’t need a home theater screen when you can have an IMAX in VR anywhere you want. You don’t need multiple physical monitors at your workstation when you can have as many as you want in mixed reality. And many appliances and other physical devices are poorly designed and overly complicated, and would be better off just reporting sensor data to augmented reality.

Office buildings. It’s going to get harder and harder to justify the cost and commute times associated with these single-use locations as we simulate our presence there better and better (see this thread for more on how physical space will reshape around spatial computing).

Travel. Some travel will continue for adventure and luxury, but will we still be traveling as much for business? So much other travel could be satisfied through immersive simulations, or embodied telepresence via drones—reaching far greater numbers of people.

That’s just a few examples—you can probably think of many others. It may happen anywhere that digital computing is tied to fixed locations, or your physical location constrains your ability to collaborate, cooperate or experience.

Is gaming the “Killer App” for spatial computing?

I won’t argue against games beings some of the most awesome experiences you can have on a Meta Quest or a Vision Pro. But like smartphones, they’re secondary to the core purpose of the device.

Spatial computers are not like a PlayStation—game consoles that just happen to be good at a few other things, like playing movies. Spatial computers add computation to our physical space and add physically-embodied experiences to virtual space. They let us realize the old dream of entering new worlds and new planes coexistent with our own.

Virtual screens will be disruptive, because they allow us to summon an infinite number of screens into VR/MR, eliminating the need to manufacture space-wasting screens. Architects will refactor homes around this.

Spatial Video can allow us to more holistically recall a past experience, share an experiences with a friend, and see the world from someone’s viewpoint. It expands the fertile territory of immersive, embodied storytelling. 2D photos and videos won’t go away, but their purpose and use cases will diverge away from spatial versions.

Games in Virtual and Mixed Reality

Rather than disrupting the game industry (as happened with mobile) — it is likely that games will be what disrupt many other forms of learning, exploring and being. And as noted earlier, it is more likely that older forms of consuming games will continue, even as we allow for new forms of entertainment.

Screens, especially larger screens, are the right form-factor for many game experiences. But now you will be able to play these games from anywhere, for the same reason that virtual screens will be instantaneous and pervasive. Each virtual screen is not simply a new way to watch old-style media, but a portal waiting to be explored and played with.

Fortnite, League of Legends and Minecraft don’t really need “VR versions” to be popular on VR devices. You can do this now with the Steam app (for iOS, so you can load it to the Vision Pro), or on the Meta Quest using Xbox Arcade or a virtual desktop application.

The more novel games will take advantage of the unique input/output characteristics of spatial computers, just as Angry Birds figured out how to make playful use of the touchscreen.

Beat Saber was one of the first to reach scale; its team figured out how to combine compelling gameplay with the unique embodied experience that virtual reality enables.

There are many more Beat-Saber-like discoveries to be made in virtual and mixed reality. Audio Trip is an example of taking the core body-movement idea to the next level, weaving it with dancing and fitness.

Cubism demonstrates how spatial environments are far better playing with 3D objects. 3D puzzles are really annoying to manipulate on a 2D screen. But in the embodied, tracked environment enabled by spatial computing, you can work with the puzzle pieces in a way that maps to what your brain has learned from physical reality.

Demeo is another game gets several things right:

It refactors the tabletop gaming experience into a digital format—not unlike how something like Hearthstone added uniquely-digital refinements to the collectible card game genre.

Demeo’s developers chose a game type that takes advantage of spatial computing—by selecting a game with a 3D play surface and figurines.

If you grew up with tabletop games (like I did), it transports you back into time to the basement gaming room you likely had as a kid—echoing the unique power of spatial computing to let you re-experience the past (as with spatial video).

Vehicle Simulators

Vehicle simulators and games based on these simulations work particularly well because you get movement without the uncanny-valley effect of teleporting or sliding around a map.

Vehicles in 2D don’t really capture the natural experience of a vehicle, which involves glancing around the side windows and using more of your peripheral vision.2 Advanced players can also incorporate physical controls (steering wheels, yoke/throttle used in aircraft) which provide direct tactile feedback—giving you just about everything you’d get from a real vehicle except the sensation of acceleration.

Applications Transformed by Games

There are new types of products that seem part-game, part-toy, and part-something-else we haven’t quite named yet.3

Rather than spatial computing disrupting games, maybe it is games that will disrupt everything else:

TRIPP

Designed to lull the user into a relaxed state, TRIPP uses a combination of flow-inducing mini-games as you float through psychedelia-influenced worlds. And while the surface of these worlds might seem trippy, the craft of a game-maker is clearly evident in the attention to detail, the visual storytelling and the immersiveness of the environments. The founders, including Nanea Reeves, have deep experience in games.

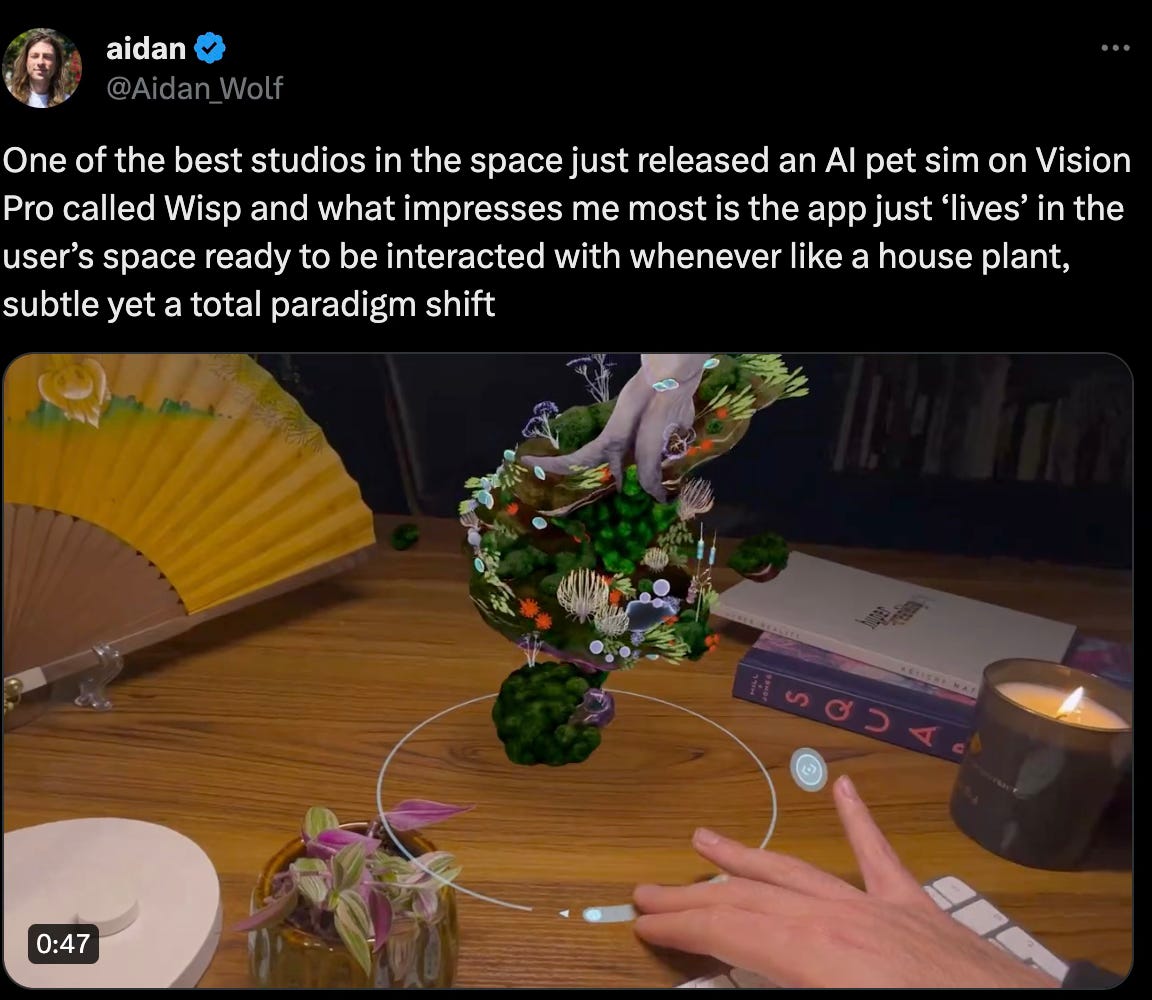

Virtual Pets

Where TRIPP brings magic into your inner life, virtual pets are an example of how apps can bring magic back into the reality we live in.

One of the more intriguing applications on the Vision Pro is Wisp by Liquid City, a virtual pet simulator. Virtual pets are a tried-and-true category in the gaming and toy markets (remember Tamagotchis?) There’s something truly enchanting about adding these playful digital holograms into our world.

Speaking whole worlds into existence

Between generative AI, creator-driven worlds, and the most recent Meta Quest 3 and Vision Pro—we’re sprinting towards a highly creative future. I’ve written about this in the past: we will some day speak whole worlds into existence.4

Just as creator-driven worlds are eating the world of gaming, it is no surprise that some of the most popular spatial computing applications are VR-native, creator-driven worlds like VRChat and Rec Room.

Creating a world isn’t simply about creating approximations of our own. The craft of game-making is about storytelling, interesting decisions, creating abstractions around the complicated, building aspirational roadmaps, and embroidering experiences with enchantment.

When you enter a world, you pass into the magic circle, where all aspects of that world—and how we relate to it—are reimagined.

Part of that includes developing new abstractions for simplifying complicated entertainment and informational substrates. We won’t just invent new types of worlds, we’ll dream up whole new ways of experiencing worlds. And these worlds need not be bounded by the physics of scarcity, and even our senses might be remixed in new synesthesias.

While spatial computing might not disrupt games or be the ultimate “killer use cases” — it’ll be the magic of games that will infuse most of everything else.

This article was an elaboration of a section on spatial computing I included in Game Development Trends in 2024: Crisis and Opportunity. Since you got to the end of this article, you’ll probably enjoy reading that one next.

Of course, on-site arcade games were eventually rendered mostly obsolete, whereas it was once the major form of delivering video games. But most on-site entertainment didn’t give people a good reason to go there, and game consoles and computers started to deliver experiences that are objectively better in nearly every way you might compare.

Current AR/VR doesn’t make use of enough peripheral vision either, probably to keep costs down, but once that becomes standard it will make a big difference to vehicle simulations.

Maybe these applications are “metaverse experiences”?

Jaron Lanier also used this phrase in a recent article in The New Yorker. His views both align—and contrast—with my own. In particular, I don’t see the evidence for the idea that games have eluded VR because gamers want to be bigger than the worlds they are in. I see quite the opposite: people love deep immersion. The issues are likely more about practical issues like ergonomics and weight, or the fact that gestures burn more calories than controllers and mice.