The Meaning of Virtual Worlds

No, this isn’t about the definition of “virtual worlds” — it is about meaning itself, and how it is conveyed, and the things people care about.

It is about games, and spatial computing, and metaverse. It is about the making the parts of virtual worlds that actually matter.

It’s virtual worlds all the way down

You don’t directly interact with the physical world; your brain generates a simulation1 of the environment around you, based on the inputs from your senses. When you rehearse something in your mind, dream, or plan for the future you are interacting with your brain’s simulation capabilities.

When we consume media—books, art, movies, games—we are invoking the power of our brain to compose a virtual world from a scarce number of inputs.

Mind the Gap

Our brain is always filling in the gaps in our experience.

Certain experiments can prove to you that this happens all day long. Cover your right eye with your hand , and then staring at the plus sign in the following image; you’ll see the red dot disappearing and reappearing as it continues its path.

Beyond our literal blind spot, we have countless cognitive and narrative blind spots that pervade our experience. Yet our brains are good at working around these gaps in perception, knowledge2 and story—filling in the parts we don’t know or don’t see into an illusion of totality.

That’s how virtual worlds work.

Long before “virtual reality” and metaverse and online games—humans created persistent virtual worlds for each other. These worlds only required the most basic set of inputs to stimulate our imaginations.

To live beyond our own minds, a virtual worlds need a way to persist. Fortunately, we don’t need a technology for this: humans are reasonably capable of transmitting virtual worlds to each others’ minds via oral storytelling, where the world is then stored in someone else’s brain.

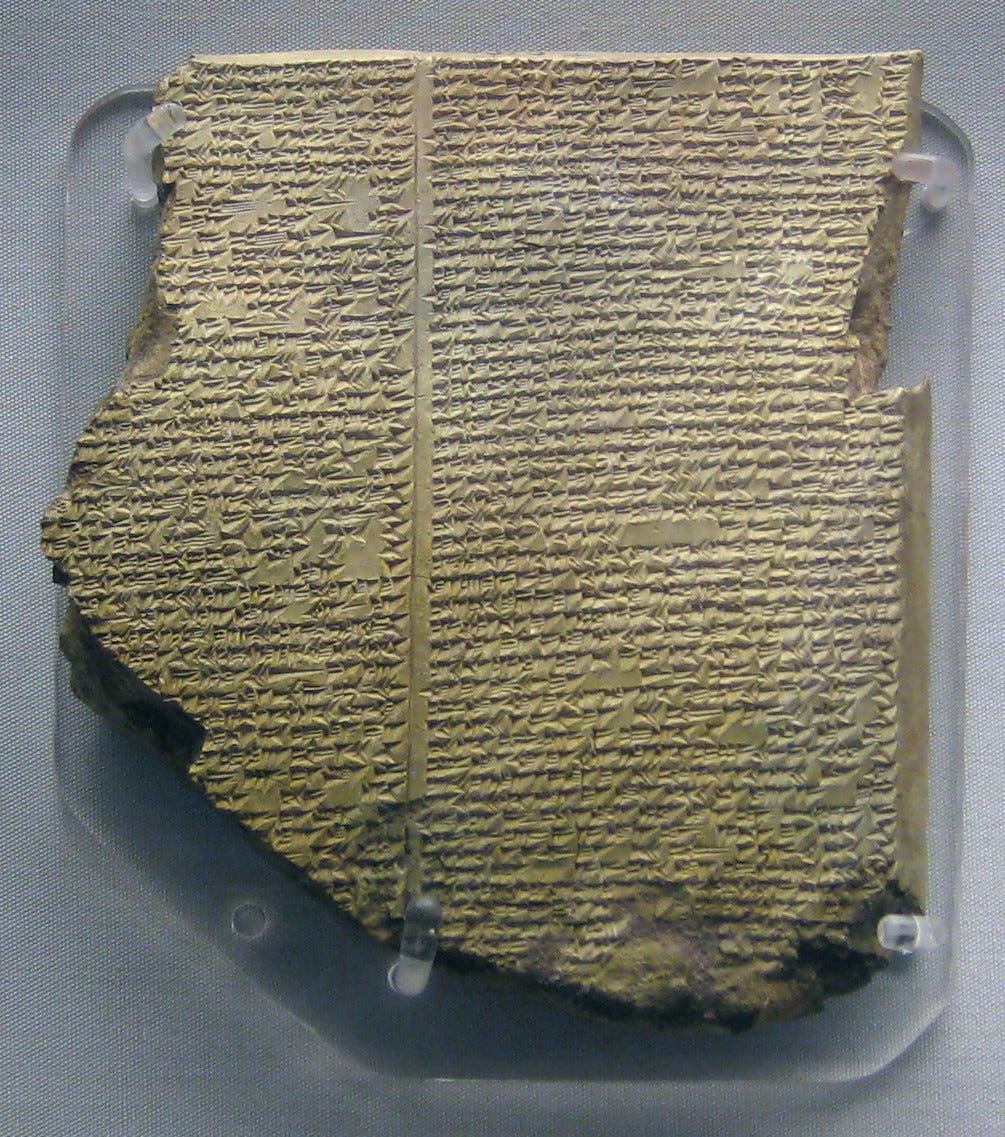

Of course, there’s a lot of scalability and accuracy problems with this. One of the first technologies that addressed this was writing on stone tablets, such as this one that contains the Epic of Gilgamesh:

Meaning-Making

Simply occupying a virtual world isn’t enough; for a virtual world to be interesting, it requires meaning.

When I talk about meaningfulness, I’m really exploring questions of “why?” Why do we do things? Why do we care? Why do we feel? Why do we exist? These questions are about purpose and intention.

The ancient Epic of Gilgamesh shows us that we’ve been curious about the same meanings for thousands of years:

The Epic explores many issues; it surely provides a Mesopotamian formulation of human predicaments and options. Most of all, the work grapples with issues of an existential nature. It talks about the powerful human drive to achieve, the value of friendship, the experience of loss, the inevitability of death. (Tzvi Abusch, The Development and Meaning of the Epic of Gilgamesh)

Achievement. Friendship. The will to survive. These ancient concerns will be familiar to you from all the forms of media you consume.

Conveying meaning begins with an artistic intention. The artist’s craft is about applying tools and techniques to communicate their intention.

Across 4 millennia, we’ve developed different technologies for transmitting virtual worlds into each others’ minds. In previous eras, these were things like amphitheaters, printing presses, movies, and television. The newest form of virtual world is the video game.

In game-making, we use things like the visual arts, sound, music, narrative structures, clever programming, core loops, progression, the “meta” and a long list of other tricks to convey meaning. But these are just the features that can be used to convey the meaning, not the meaning itself.3

As Antoine de Saint-Exupéry wrote: “If you want to build a ship, don’t drum up the men to gather wood, divide the work, and give orders. Instead, teach them to yearn for the vast and endless sea.” This is the difference between simply doing stuff, and finding meaning.

Some but not all virtual worlds are games. But all virtual worlds need to have meaning, or they’re just technologies bereft of intention.

Once you’ve determined the meaning of your virtual world, there’s really just two big questions to determine:

What parts do I need to include to convey my meaning

What parts can I leave out to focus on my meaning

In my experience, people are overly worried about the former, and not the latter.

Remember: our brain is good at managing the blind spots. Trust humans to form meaning from the parts that are important. Indeed, leaving only the parts that convey the meaning are how you focus attention in your virtual world on the aspects that matter most.

The Simulation Hypothesis is real in this obvious way; at a minimum, we’re living in our own simulation of the physical reality beyond our mind.

Perhaps this is partly what explains the Dunning-Kruger Effect (the overestimation of one’s competence despite a lack of knowledge).

Ironically, meaningfulness is often forgotten when someone brings up “gamification.” These efforts usually seek to apply the technologies of game-making (particularly the attention-generating features) in a non-game context, but forget the critical importance of meaning-making. You could also say the same thing about many examples of the “metaverse” discussed since the end of 2021—too often described as a convergence of technologies for things like presence, embodied experience, visualization, real-time interaction—but without the intention or meaning behind these applications.

Brilliant as always, very thought provoking for perception of reality. I think the same way like you about living in simulation of our own.