Games and Attention: the Economics

Creating for the Most Important Media Category in 2024

The business of games has always been about attention. It doesn’t matter if your game is free-to-play or premium; multiplayer or single-player; “live services” entertainment or offline. This article explains why this is the most important aspect of building a sustainable1 game business, regardless of your business model.

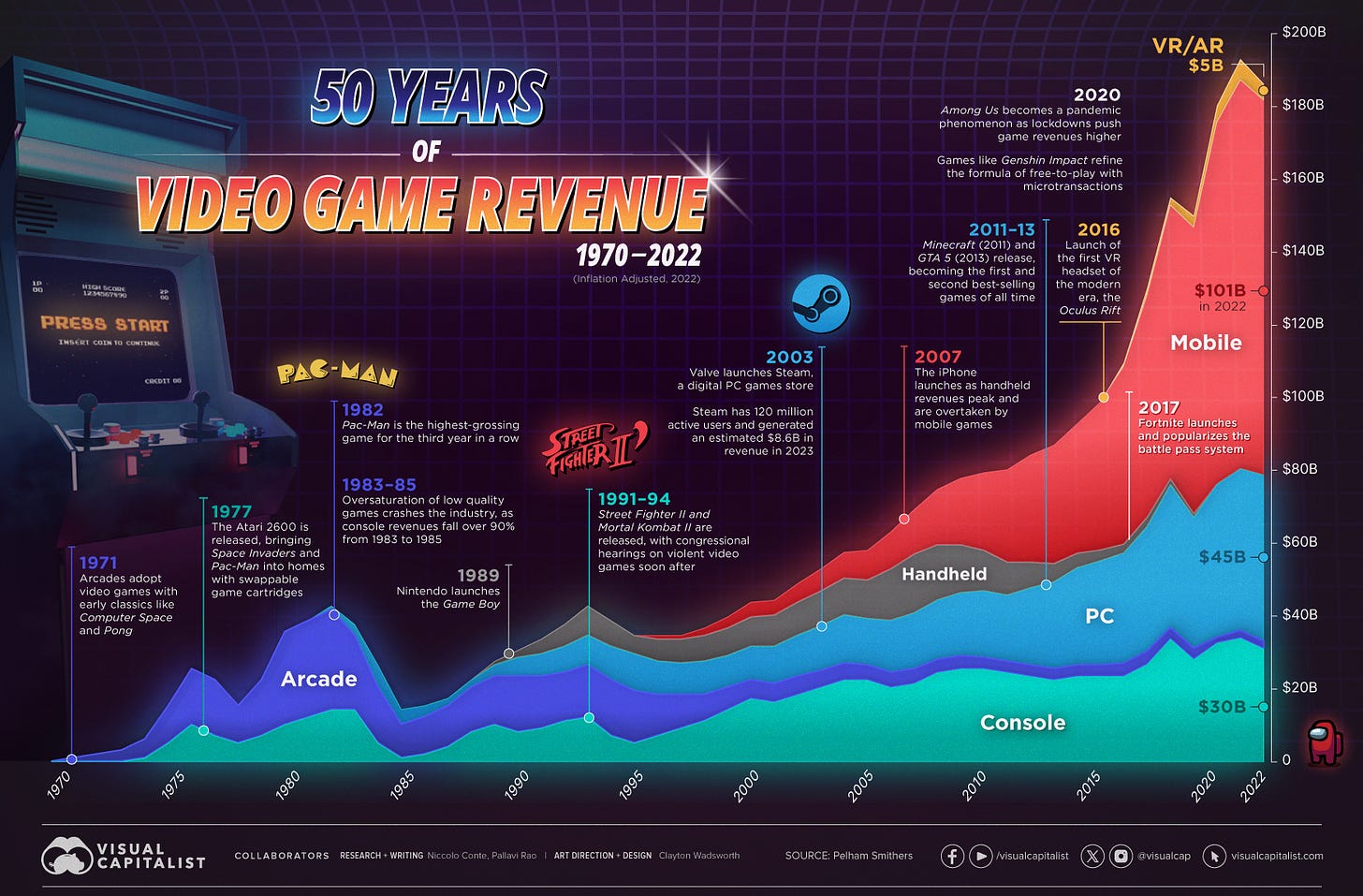

An updated version of a famous graph of game industry revenue has been floating around:

I used the original version of this chart in my article on my 3-part series on the economics of games nearly three years ago, so I thought it was time to review my findings and forecasts and see how they stacked up over time.

Live Services Eating the World

Live services games continue to eat the world of gaming. The reason for this is that live services are particularly focused on driving engagement. Engagement is basically manager-speak for consistently getting and keeping someone’s attention.

One data point: Electronic Arts recently reported that live services games are 73% of their revenue. And EA is one of the oldest game publishers, with a portfolio of non-live-services games. Overall, the average across of the entire industry is likely much higher, perhaps 85-90%.

Continuing the EA example, even in the case of their games that are not live services—they generally benefit from strong franchise recognition. When you buy a game’s sequel because you loved the time you spent in a previous title, that’s another way of extending your experience; it’s like compound interest on the original attention you spent.

Digital Collectibles

The “digital collectibles” market (at least as I defined it) is taking a while to materialize. It definitely hasn’t happened as substantial scale yet—at least beyond games like Magic the Gathering Arena who are using non-NFT technology to continue to extend their collectible gaming market. (There was the brief explosion of activity around Axie Infinity, but it isn’t apparent that this wasn’t almost entirely speculation-driven; the players who did participate were likely doing so for largely extrinsic reasons).

Something I got a bit wrong is the trajectory that “digital collectibles first” game companies would take. What’s become apparent is that after all the grift in the NFT market, people won’t trust anyone to get a game—let alone a whole game economy—over the finish line until they actually ship it.2 They want to see finished products before spending money; and when they do, it’ll likely have to follow the same value proposition as something like MtG, where one can derive a lot of value from an $11 booster pack purchase rather than 1 ETH one-of-a-kinds; games of scarcity will always have their “whales” whether they’re free-to-play or blockchain-based, but the price of participation can’t be unreasonably high relative to other forms of entertainment. The lesson: build games, not unachievable dreams.

To be fair, building great games often takes years and it also took many years before free-to-play found its stride; based on a number of teams I’ve seen building digital collectibles products on Beamable, I think we could see some great products in the next year.

The companies who will succeed in this category will be those who are heads-down, focused on great gameplay ahead of everything else. Here are a few I’m aware of: Azra Games, Mystery Society, Shrapnel, Wildcard Alliance.

Live Services != Free-to-Play

Free-to-play and live services are not the same thing. Live services features like competitive play, cooperative multiplayer, tournament, leaderboards, matchmaking—and even events and content updates—are all fantastic ways of delivering value and capturing attention. Even single-player, non-monetized experiences can absorb some of these features. The value of this attention is realized as the game ships DLC, or years later when the sequel emerges—or perhaps through the halo-effect granted to the studio’s brand.

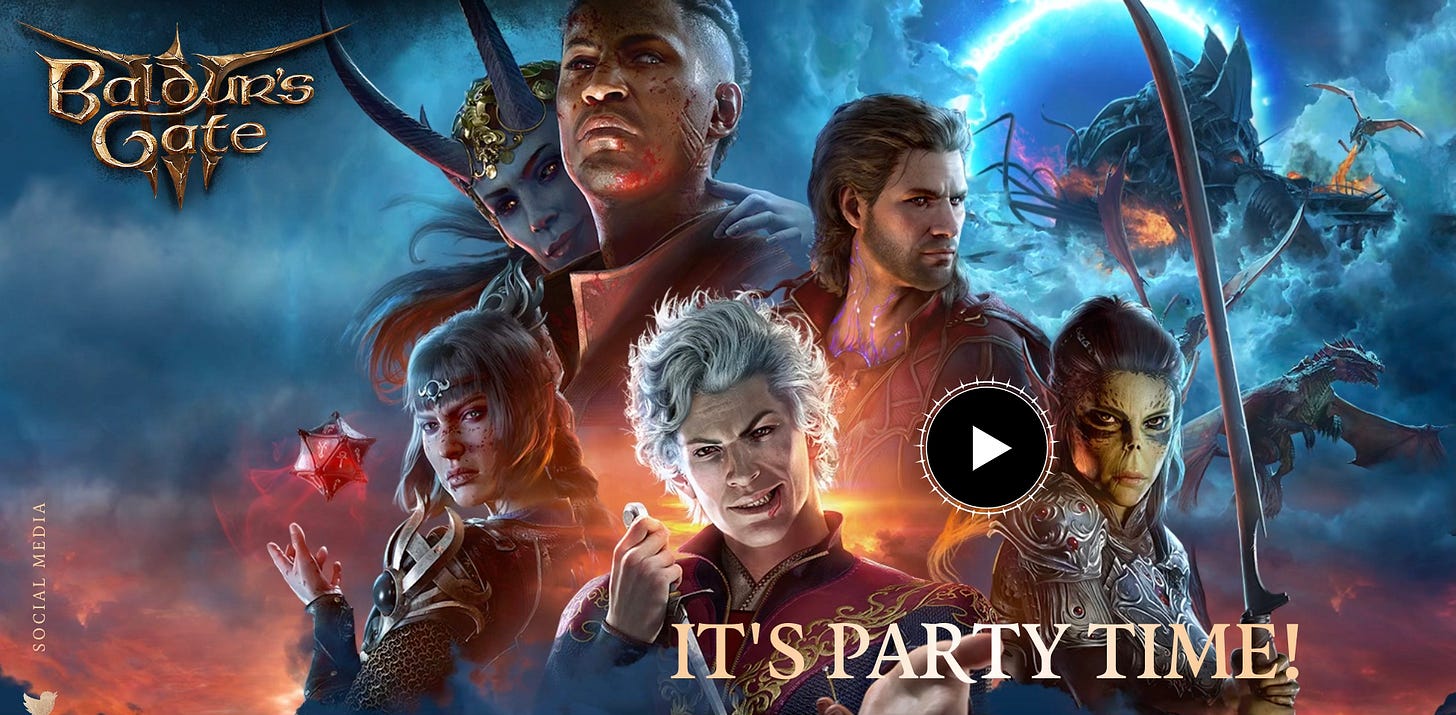

It’s Party Time

My favorite game from 2023, Baldur’s Gate 33, is a great example of this. BG3 also demonstrates a mode of play that I see getting increasingly popular: families and couples who play together. As people who grew up with games continue to age and find themselves in relationships, it is cooperative multiplayer gaming that will push aside other date-night activities—yes, even the Netflix and Chill nights.

Sustainable Growth

In 2023 we saw the impact of changes to the mobile advertising ecosystem: it became harder than ever to acquire the right customers at scale, which pinched profit, which resulted in huge losses of capital. Case-in-point: Marvel Snap is a wonderful game, but the publisher couldn’t turn a profit despite hundreds of millions invested (fortunately, the developer Second Dinner, appears able to operate the game without the publisher’s ongoing support).

As Eric Seufert noted in his article, The Only Growth Metric that Matters, those who over-optimize on one or two holy-grail metrics (like Return on Ad Spend) could be setting themselves up for costly failures. There are too many metrics to consider:

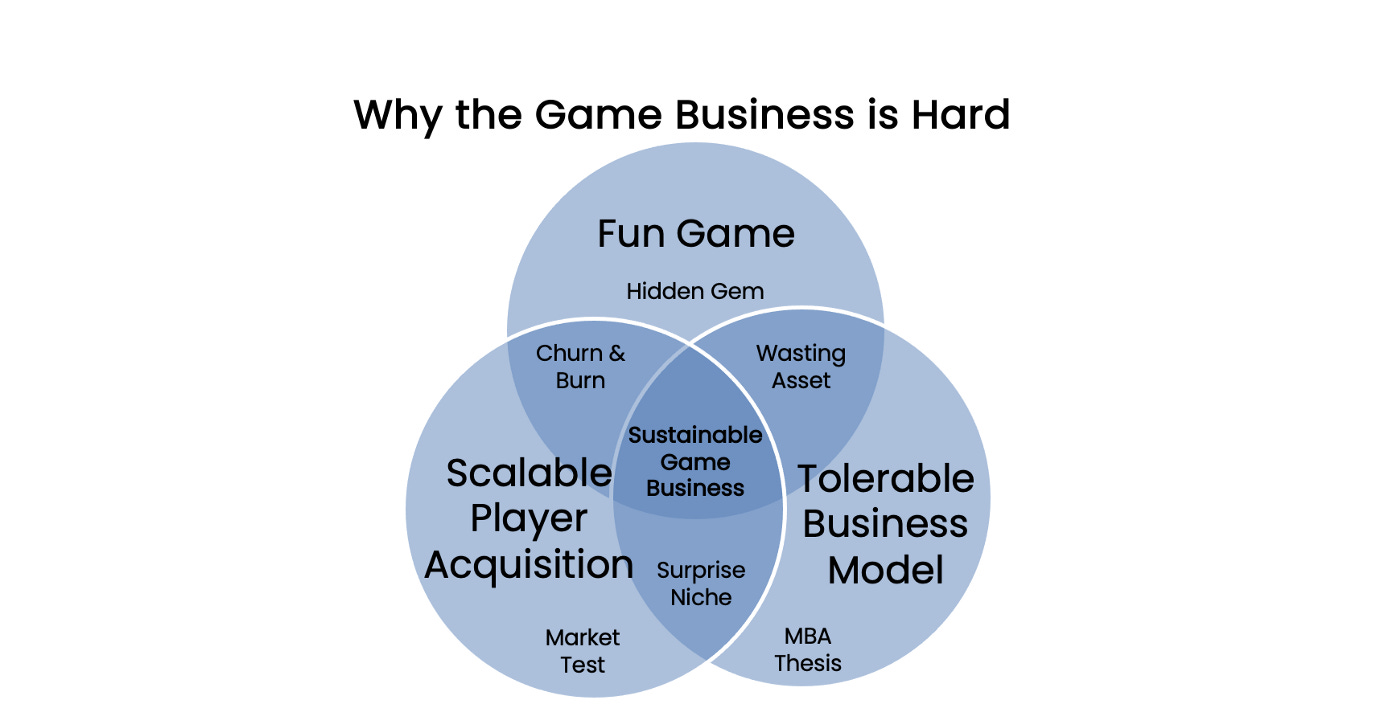

That said, I stand by the idea that gaining and maintaining attention is what matters if you want a sustainable business. I wrote about this in Why Scaling Games is Hard:

Further Reading

If you enjoyed my article, you might like the longer three-part series on the economics of games. It all remains relevant today.

If you have time for a short article or two, you’ll probably like these two: Why Scaling Games is Hard, as well as its follow-up on competitive dynamics: Why the Games Business is Getting Harder.

To be clear, I’m a big believer in both choice and artistic expression. You don’t have to make a sustainable business. You could create a game as a piece of art, and not care about any of this. Or you could create a studio to make your idea, ship it, and then shut the studio down if you feel you accomplished everything you wanted. These sort of choices aren’t inherently wrong, but this article is about people who are focused on sustainable gaming businesses—those that can grow, attracting customers, capital and talented staff over decades.

This is not just a function of blockchain-based games; Star Citizen, now funded by over $600M of backers—and is certainly a “digital collectibles” game albeit not a blockchain-based one, is a cautionary tale to fans who don’t fully appreciate how hard and complicated it is to make ambitious games. Unfortunately, this has also eroded the viability of platforms like Kickstarter as a place to fund games, as people have learned just how hard games are to create.

I loved BG3 so much that I got Divinity Original Sin 2 and played through it over the holidays. Also a wonderful game; I hadn’t played a Larian title since the original Divine Divinity—I was missing so much of their fine work!