What It Takes for a Mobile Game to Live Long and Prosper

Ten years ago, Star Trek Timelines launched. Here’s why most online games never make it this far—and what we built differently.

Star Trek Timelines just celebrated its 10-year anniversary. I led the creation of this game at Disruptor Beam—later selling it to Tilting Point in 2020 when my cofounders and I decided to pivot towards Beamable, a software platform for the backend of game development.

A decade is a long time for any online game. According to SuperScale’s “Good Games Don’t Die” research, 83% of mobile games fail within three years. 76% hit peak revenue within year one. A mere 5% receive support beyond seven years. The graveyard of mobile gaming is vast and largely unmarked.

The games that survive a decade? You can count them on your fingers. Candy Crush. Clash of Clans. Temple Run. And now, Star Trek Timelines—celebrating its anniversary with a massive Borg-themed mega-event and John de Lancie reprising Q for a livestream, and a community that remains passionately engaged.

What makes a game endure? I’ve come to believe it comes down to a few essential principles. But for Star Trek Timelines specifically, I think the answer starts with authenticity.

The Final Frontier Isn’t Space—It’s Time

Star Trek has never really been about space battles. Yes, the Enterprise fires phasers and photon torpedoes. But the soul of Star Trek is philosophy, exploration, engineering, diplomacy, and the spirit of adventure. It’s Kirk talking a computer into destroying itself with a logical paradox. It’s Picard choosing words over weapons. It’s engineers solving impossible problems under impossible deadlines.

Above: Working with John de Lancie, the actor behind Q, to write and produce a new opening monologue in the tradition of “Space, the Final Frontier” was one of the most fun experiences I had creating Star Trek Timelines.

When we pitched Star Trek Timelines to CBS, we needed to solve a fundamental problem: how do you make a game that spans sixty years of television history feel coherent? But the deeper question was: how do you make it feel authentically Star Trek?

The answer was the temporal anomaly—but not just as a narrative device. We reimagined the frontier itself. Space had been explored across nine television series. The new frontier would be time.

Q appears to explain that time itself has become unstable, throwing people, places, and starships from every era into a single fractured reality. The time portal itself was a deliberate nod to “The City on the Edge of Forever”—widely considered the greatest Star Trek episode ever made, and a story fundamentally about the weight of choices across time. By weaving the Q Continuum into the storyline, we gave the game an omniscient narrator who could be playful, menacing, philosophical, and unpredictable—just like the best Star Trek episodes.

This wasn’t just narrative convenience. It was a design philosophy rooted in what makes Star Trek resonate with fans across generations. The game reflects that Kirk can serve alongside Janeway not as fan service, but as a genuine exploration of what happens when different eras of Starfleet philosophy collide. A Constitution-class starship can encounter a Borg Cube, and the question becomes: what do we learn from this? Mirror Universe versions of beloved characters exist alongside their prime counterparts, raising questions about choice and identity that Star Trek has always explored.

The mechanics reinforced this authenticity. Away missions aren’t just combat—they’re scenarios requiring diplomacy, science, engineering, medicine, and command skills. Characters succeed based on their actual competencies from the shows. Scotty solves engineering problems. Troi handles diplomacy. Data processes information. The game rewards players for understanding who these characters actually are, not just collecting the most powerful fighters.

A Framework That Can Grow Forever

We built the game knowing we’d need to continuously add characters from whatever new Star Trek content emerged. When Discovery launched in 2017, we added those characters within weeks. Same with Picard, Lower Decks, and Strange New Worlds. The narrative framework we established on day one has accommodated over 1,800 characters across every series, film, and even the novels and comics.

Too many games paint themselves into corners. They create fixed worlds that can’t evolve. A live game needs room to grow indefinitely—and that growth needs to feel organic, not forced. Because we built time itself as the frontier, every new Star Trek series simply becomes another era contributing to the temporal crisis. The framework never breaks.

Live Ops Is the Game

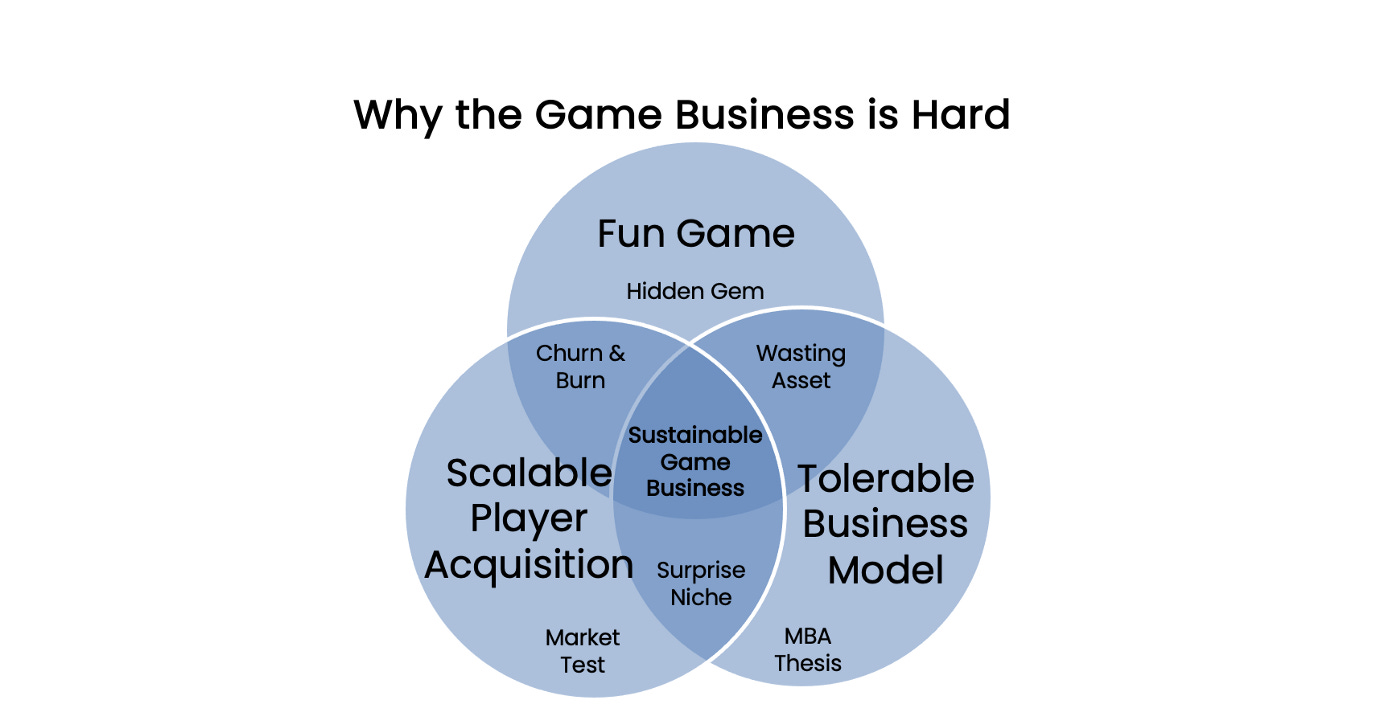

I’ve written before about why scaling games is hard. Making something fun is one of the hardest creative challenges there is. But even a fun game faces the challenge of business model alignment—will your audience tolerate how you make money? And then there’s scalable player acquisition: can you find new players without spending more than they’re worth?

Games that nail all three—fun, tolerable monetization, and scalable acquisition—become sustainable businesses.

Fun games that are unable to accomplish the latter two become a “hidden gem” that few discover, a “wasting asset” that briefly monetizes but never grows, or a “churn and burn” that players enjoy for moments but leave before the game turns a profit.

Star Trek Timelines worked because it fired on all three cylinders, but it also worked because we understood that live ops isn’t something you bolt onto a finished game—it is the game.

Star Trek Timelines launched with away missions and ship battles. But over the years, the team added The Gauntlet (a competitive mode where Q pits players against each other), Voyages (extended expeditions that became the primary source of rare characters), Fleets and Squadrons (enabling community formation), and most recently, Goyages—a mashup of Voyage and Gauntlet mechanics for competitive weekends.

Each of these features extended player engagement in different ways. Some appealed to collectors. Some to competitive players. Some to those who valued social connection. A live game needs multiple hooks because player motivations evolve over time.

This is why we built such sophisticated backend infrastructure at Disruptor Beam—tools for content delivery, event management, in-game merchandising, CRM, and analytics. When we pivoted to Beamable in 2020, we essentially said: the technology we built to run Star Trek Timelines for millions of players is now available to any developer who wants it. That infrastructure is what makes continuous evolution possible.

Community Is Infrastructure

A game can have perfect mechanics and still fail. What separates the survivors is community.

From early on, we invested in features that connected players to each other. Fleets of up to 50 players working toward shared goals. Starbases that required collaborative upgrades. Leaderboards that created friendly competition between groups. These aren’t just features—they’re the social fabric that keeps people coming back even when they’ve collected most of the characters they wanted.

But the most important community features aren’t always built by the developers. I’ve watched Star Trek Timelines communities form on Discord, create their own wikis (DataCore is extraordinary), develop optimization tools, and organize events outside the game entirely. The best thing a developer can do is create the conditions for this to happen and then stay out of the way.

John de Lancie’s involvement exemplified how seriously we took authenticity and community together. Having him voice Q was table stakes. Having him participate in design decisions, engage with players directly, and return for the 10th anniversary livestream? That’s what turns players into advocates. Q isn’t just a character in the game—he’s the narrative thread that holds everything together, and having de Lancie invest in that role made it real.

The Math of Survival in an Increasingly Difficult Market

Here’s a reality most people outside the industry don’t appreciate: keeping a mobile game running costs real money every single day. Servers. Customer support. Content creation. Compliance. Platform fees. A game that generates $10,000 a day sounds successful until you realize it costs $15,000 a day to operate.

The SuperScale research found that 43% of games are killed in development before they even launch.1 Of those that do launch, most never achieve sustainable economics. 78% of mobile game developers prefer working on new titles rather than supporting existing ones—creating a catch-22 where games are abandoned precisely when they need the most nurturing.

And as I explored in why the game business is getting harder, the competitive dynamics have intensified dramatically. Customer power has increased—players can vote with their wallets and voice opinions online in ways that shape distribution. The funding landscape has transformed, with numerous alternatives to traditional publisher deals. Capital has flooded into the industry, making competition fiercer than ever.

The 83% failure rate within three years isn’t because those games were bad. Many were well-designed, beautifully crafted experiences. They failed because the economics didn’t work. Revenue declined faster than costs could be cut. The team moved on to the next project. The servers went dark.

Star Trek Timelines exceeded $100 million in lifetime revenue by 2020. That sounds impressive—and it is—but what matters more is that revenue remained sufficient to fund continued development year after year. The web shop implemented (through Xsolla) generates nearly 25% of revenue, providing a more sustainable margin than app store purchases alone.

Sustainable economics require respecting your players. The most successful free-to-play games create genuine value exchanges. Players who spend money feel they’re getting something worthwhile, not being exploited. Players who don’t spend still have meaningful experiences. Get this balance wrong and your community evaporates.

What Ten Years Means in 2026

Looking at where the industry stands today makes Star Trek Timelines’ survival even more remarkable. According to Sensor Tower’s State of Mobile Gaming 2025 report, mobile gaming is generating over $100 billion annually, but downloads have been declining since 2021. The old “build-launch-repeat” model has given way to live operations as the dominant paradigm. Players now expect games that evolve continuously.

The winners in 2025 and 2026 share certain characteristics: deep progression mechanics, seasonal events, strong retention strategies, and what analysts call “building roots, not spikes.” Games like Last War: Survival and Whiteout Survival have joined the billion-dollar club by mastering these techniques. Cross-platform play has become expected rather than exceptional. AI is beginning to transform everything from NPC behavior to personalized challenges.

But the fundamentals haven’t changed. Depth matters. Players want games they can grow into, not just pass through. In a world where switching costs are rising—social graphs, daily streaks, invested progression—the games that survive are the ones that give players reasons to stay.

Star Trek Timelines was doing this before it had a name. The temporal crisis narrative gave players a universe worth exploring. The crew collection system created investment that deepened over time. The fleet mechanics built social bonds that made leaving feel like abandoning friends. The continuous content updates from new Star Trek series kept the universe feeling alive.

What Ten Years Teaches You

I started creating online games when I was 13, building Space Empire Elite for Atari ST bulletin boards. The technology has changed beyond recognition, but some truths remain constant.

Players want to feel that their time matters. They want to connect with others who share their passions. They want to be surprised and delighted by new content. They want to trust that the world they’re investing in will still exist tomorrow.

Most games fail not because they’re bad, but because they’re built as products rather than services. They launch, they generate some revenue, and then they’re abandoned for the next project. The developers move on. The players are left with nothing.

Star Trek Timelines took a different path. It was built to evolve. It was built with infrastructure that could scale. It was built with a community at its center. It was built to feel authentically Star Trek—not just in its characters and ships, but in its values: exploration, cooperation, the idea that the unknown is something to embrace rather than fear. And crucially, when I could no longer give it the attention it deserved, it was transitioned to a team that could.

Watching it celebrate a decade with Borg events and Q livestreams and thousands of engaged players—that’s the outcome I hoped for when we started this journey. In an industry where 83% of games don’t see their third birthday, reaching ten years puts Star Trek Timelines in genuinely rare company.

The final frontier turned out to be time—in more ways than one.

Live long and prosper, indeed. 🖖

Further Reading

Why Scaling Games is Hard, about the three main factors in the way of making a game succeed: it has to be fun, it has to have a tolerable business model, and it has to have scalable player acquisition.

Why the Games Business is Getting Harder, a “five forces of competition” analysis of the game industry, a la Michael Porter.

This number seems awfully low, really. Anecdotally: when I speak to people in the industry, it’s more like 80% when you consider games greenlit that imply fail to reach the finish line in development.