Games as Products, Games as Platforms

The metaverse we have: and it’s the part of gaming that’s actually growing

Nobody wants to hear the word “metaverse” anymore: and that’s exactly why it’s worth revisiting.

The term got buried under the weight of Meta’s $90 billion in Reality Labs losses, a wave of failed VR social apps, and a crypto winter that froze the NFT-powered virtual land speculation that briefly passed for a business model. By 2024, saying “metaverse” in a pitch meeting was roughly as popular as saying “blockchain” in a game design document. The eye-rolls were justified: the hype cycle promised a Ready Player One future and delivered corporate avatars with no legs.

But the concept underneath the hype — the idea that people will increasingly live, create, and connect inside shared digital worlds — didn’t go anywhere. It just showed up in places that nobody was calling “the metaverse.”

A couple years ago, I gave a talk at Gamescom Congress where I argued that the metaverse isn’t a particular application—it’s the fact that we can take our identity and live in imaginary realms. I traced the lineage back to Dungeons & Dragons, which I called the first real metaverse: a space where shared imagination and storytelling were the substrate, and technology was just the delivery mechanism.1 I argued that AI wouldn’t merely improve games; it would transform civilization’s relationship with creation itself. (You can watch the full talk here.)

That was 2023. Since then, Meta has redirected its R&D spend according to this vision. Meta laid off over 1,500 Reality Labs employees in January 2026 alone, shuttering studios like Twisted Pixel, Sanzaru, and Armature: the teams behind some of Quest’s best VR games. Where they are investing: their $135 billion in planned 2026 CapEx is pouring into AI infrastructure, not virtual worlds. Ray-Ban Meta smart glasses sold over 7 million units in 2025 (tripling year-over-year) while Quest VR sales fell 30%. And at Meta Connect 2025, they demonstrated Horizon Studio’s AI-powered world building: fully immersive 3D worlds generated from natural language prompts. Zuckerberg didn’t mention the word “metaverse” once during his Q4 2025 earnings remarks. He talked about AI.

The message is clear: even the company that bet its name on the metaverse now believes the path to shared digital worlds runs through AI-powered creation, not VR headsets.

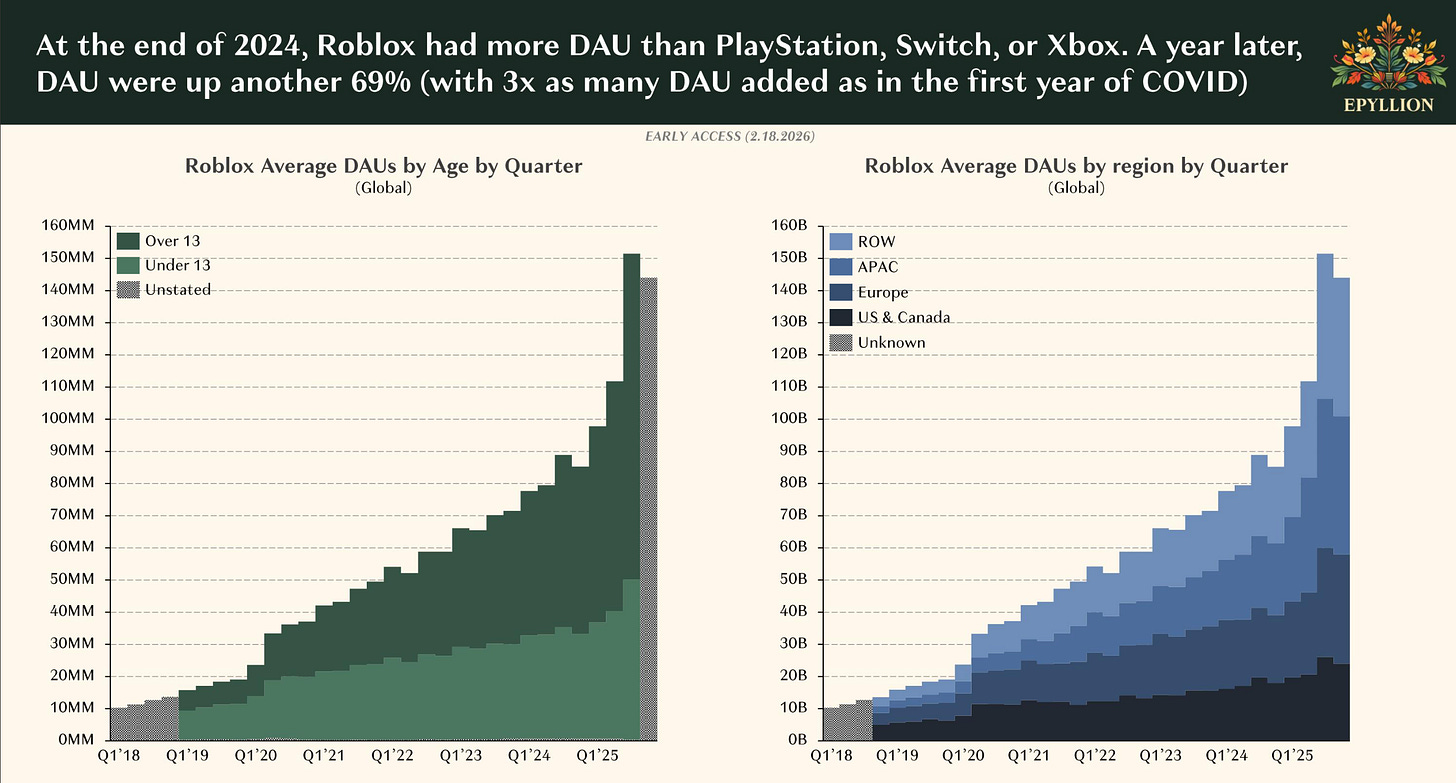

Meanwhile, Roblox just reported 144 million daily active users, up 69% year-over-year. Bookings hit $7.76 billion for 2025, up 55%. They paid creators over $1.5 billion. Minecraft, the other pillar of shared-world creation, just did something the modding community has wanted for a decade: fully deobfuscated its Java Edition source code, making the game’s architecture readable and extensible by anyone.2

The metaverse arrived. It just looks like platforms where people build things together.

The Composition Crisis

Matt Ball’s State of Video Gaming in 2026 confirms what the creator economy framework has been predicting for years, but it also reveals something more uncomfortable. Global games content sales hit $195.6 billion, an all-time record. Growth came simultaneously across mobile, console, and PC. But underneath the revenue headline, the foundations are shifting in ways the industry hasn’t fully reckoned with.

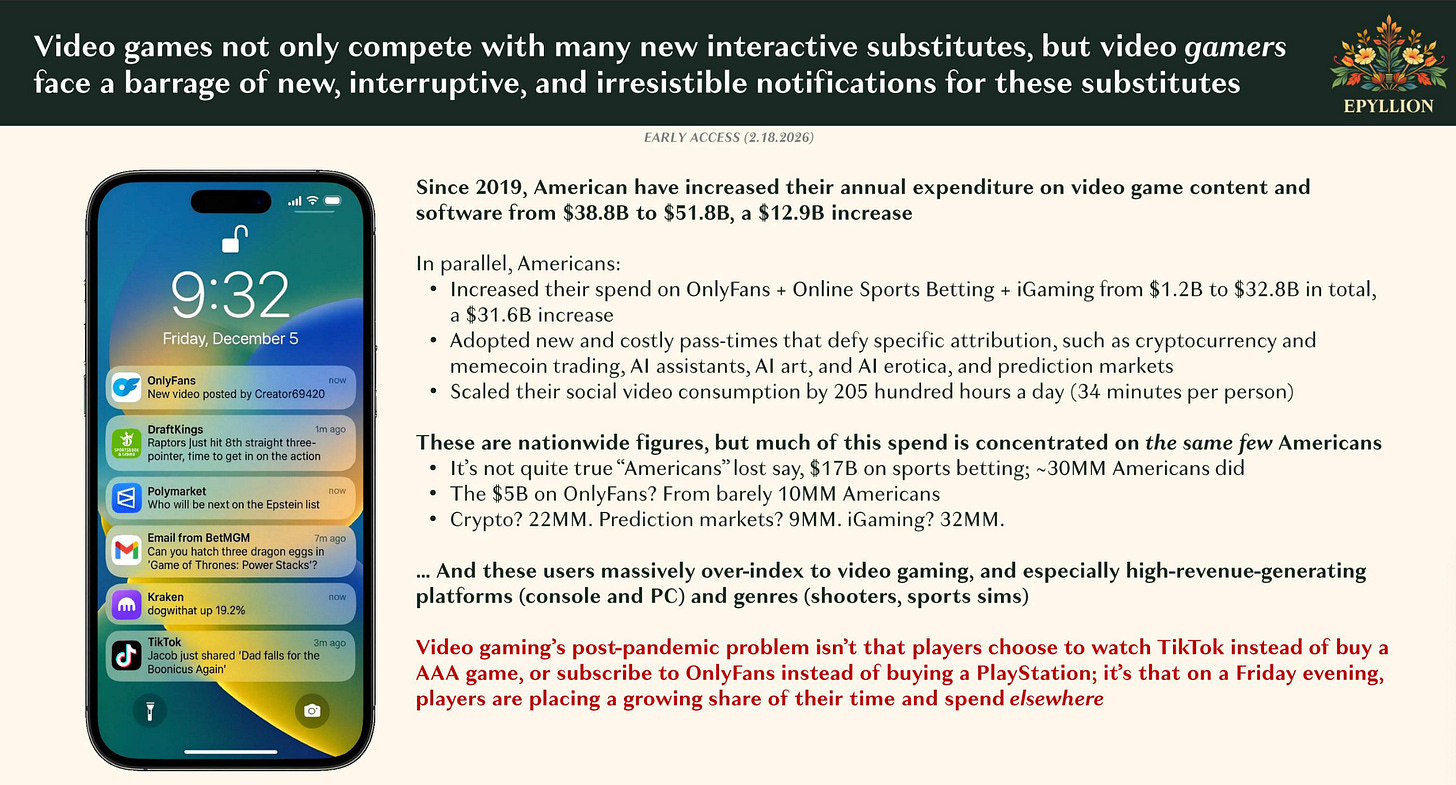

U.S. player participation has fallen below pre-pandemic levels. Mobile gaming time spent has tumbled. Gaming has been losing the battle for user attention for half a decade: not to some exotic new medium, but to the existing internet. To short-form video. To prediction markets. To memecoins. To creator porn. To the infinite scroll.

Ball frames this as an identity crisis. I’d frame it differently. It’s a composition crisis.

I’ve written before that composability is the most powerful creative force in the universe: that life itself is about information, not energy, and that what we can accomplish together through composition and recombination always exceeds what any one of us can build alone. DJ sampling, TikTok duets, Minecraft mods that spawned entirely new genres like DOTA and Counter-Strike—these aren’t just cultural phenomena. They’re expressions of a fundamental principle: the aggregate emergent output of many participants, composing and recombining shared primitives, will always outpace the output of a few specialists working in isolation.

Gaming’s $196 billion is largely built on the specialist model. Professional teams spending years and hundreds of millions of dollars building individual products for audiences that consume them. That model produces extraordinary craft: and I mean that sincerely; the storytelling, artistry, and design in the best games represent a pinnacle of human creative achievement. But it’s a model that produces scarcity, not abundance. And the attention economy doesn’t reward scarcity. It rewards the continuous novelty that only comes from massive creative participation.

This is why attention is migrating. Not because games are getting worse, but because everything else is getting more participatory.

The Dopamine Spectrum

Consider the competitive landscape through this lens.

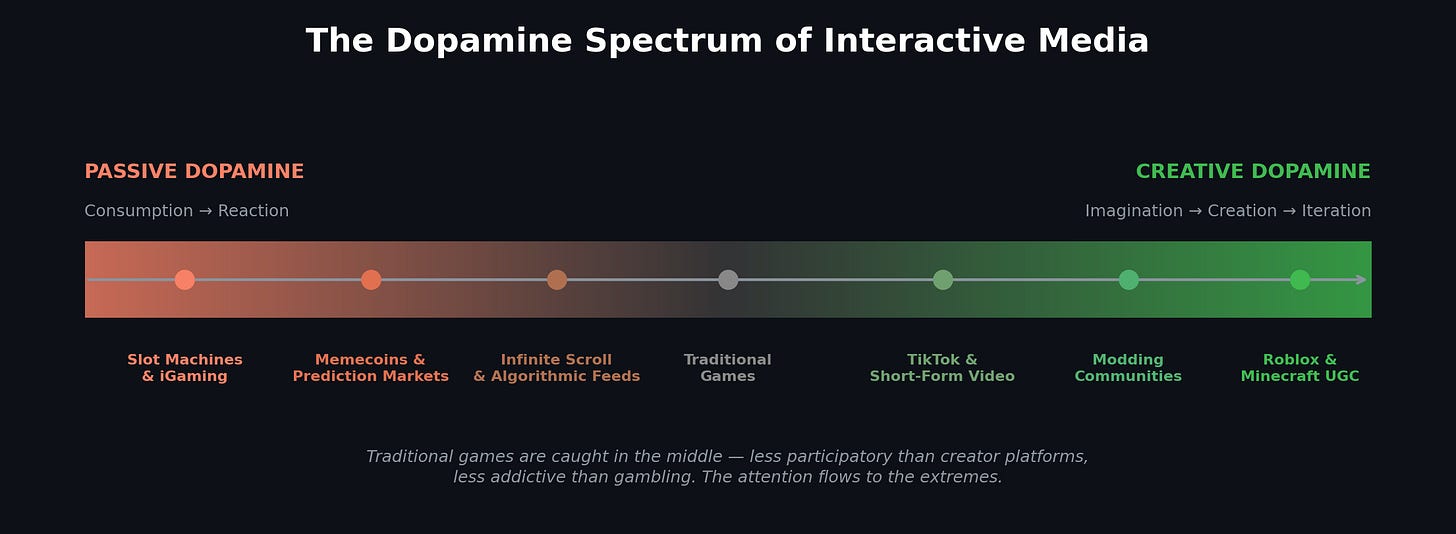

“Interactive Media”—an old term that is a good way of describing the current landscape that gaming now competes within—is worth reclaiming. The competition for attention is coming from interactive experiences that don’t look like games at all, but that run on the same dopamine loops.

TikTok users spend an average of 35 hours per month on the platform. The engagement rate on gaming content there—6.4%—dwarfs Instagram and YouTube. Gaming videos on TikTok have accumulated 200 billion views. But TikTok isn’t competing with games by being a better game. It’s competing by being a better composition engine. Anyone can make a TikTok. The loop between having an idea and publishing it is measured in minutes.

Online gambling hit $116 billion in 2026, growing at nearly 11% annually. Prediction markets processed over $20 billion in volume through Polymarket alone in 2025, with CNN and CNBC signing exclusive data deals that transformed what was a crypto niche into mainstream infrastructure. Memecoins on Solana compress the speculation-to-dopamine cycle into 10-minute intervals, replicating the neurochemical pull of slot machines on a 24/7 mobile-accessible platform.

These aren’t traditional competitors to gaming. But they all share a common architecture: they give participants an active role. You don’t just consume a prediction market; you express a view and watch it play out. You don’t just watch a TikTok: you duet it, remix it, respond to it. Even the memecoin speculators are participating in a loop of creation and iteration, however degenerate the output.

There’s a spectrum here worth noticing. At one end, you have media that hijacks dopamine through pure consumption: the infinite scroll, the algorithmic feed optimized for watch time. At the other end, you have media that generates dopamine through creation the satisfaction of building something, improving it, sharing it, watching others engage with it. UGC platforms like Roblox and Minecraft sit squarely at the creation end. They offer arguably the healthiest version of the dopamine cycle in interactive media: the feedback loop of imagination, iteration, and improvement.

Gaming’s consumption model—where professionals make and audiences play—is getting squeezed from both sides. The passive-dopamine end is dominated by social feeds and gambling. The creative-dopamine end is dominated by platforms that let people build. The traditional game, where you play someone else’s content, is losing the attention war to experiences that give people something to do, not just something to experience.

300 Million Creators

But there’s a counterpoint inside Ball’s own data, and it tells a completely different story.

Roblox’s numbers are staggering not because of their absolute size, but because of their trajectory and structure. 144 million DAUs. 35 billion engagement hours in Q4 alone, up 88% year-over-year. Revenue growing 43% while the broader industry fights for single-digit growth. International expansion driving bookings up 96% in Asia-Pacific, 700% in Indonesia, 160% in Japan.

And here’s the structural part that matters: 12.3 million monthly active developers in Roblox Studio. Over 44 million published experiences. The top 1,000 creators averaged $1.3 million in earnings, up 50% year-over-year. Roblox is guiding to $8.28–$8.55 billion in bookings for 2026 and $1.6–$1.8 billion in free cash flow.

This is what the Creator Era looks like when a platform actually commits to it. Not as a feature bolted onto an existing product, but as the fundamental architecture. Roblox’s 15-year journey, which I’ve referenced before as an example of the long, painful work of reducing friction between creative conception and execution, is producing results that make the rest of the industry’s growth look anemic.

The risk, of course, is that this is a massive walled garden. Roblox’s creator economy exists entirely within Roblox. The tools, the distribution, the monetization, the audience: all controlled by a single platform. For a thesis built on composability, that’s a tension worth naming. True composability means interoperability: the ability to combine elements across systems, to build on primitives that aren’t owned by any single gatekeeper. Roblox is proving the creator model works. Whether they—or anyone—will make it open is a different question, and arguably the more important one.

And they’re accelerating the tools that drive it. In February 2026, Roblox announced their Cube Foundation Model: what they’re calling “4D generation.” It’s not just AI-generated 3D assets. It generates functional, interactive objects from natural language prompts: a car with spinning wheels, a character with animation behaviors, objects with physics properties. During early access testing, players generated over 160,000 objects, and experiences using the tool saw a 64% increase in average play time. Their AI Studio Assistant now operates as a native MCP server, the same Model Context Protocol that’s becoming a standard for agentic tool integration: enabling multi-step task execution, automated debugging across entire projects, and direct integration with design tools like Figma and Blockade Labs.

No other major engine natively supports this architecture. It’s agentic engineering applied to creator tools at platform scale.

I built Chessmata, a chess platform where humans, AI agents, and engines participate as equal members of a shared ecosystem — in a weekend using agentic processes. The entire content pipeline used three orchestrated approaches: generative 3D through Meshy AI, procedural generation through natural language, and autonomous asset discovery. The bottleneck wasn’t engineering capacity. It was imagination. But that was a weekend project by a single person. Roblox is deploying this paradigm across a platform with 144 million daily users and 12 million active developers. The implications compound in ways that are hard to overstate.

Minecraft is approaching the same inflection from a different angle. The December 2025 deobfuscation of Java Edition — making the game’s source code fully readable with actual variable names instead of cryptic mappings2 — is arguably the most significant modding ecosystem event in the game’s history. Within 30 days, both Fabric and NeoForge had published migration guides and alpha builds. This didn’t make headlines the way Project Genie did, but its structural significance is comparable: it collapsed the barrier between understanding how the game works and being able to modify it. Combined with the Vibrant Visuals graphics overhaul moving Java Edition to Vulkan, and the ongoing development of AI agents like NVIDIA’s Voyager that learn to play and build autonomously within Minecraft worlds, you’re looking at a platform that’s becoming dramatically more accessible to both human and AI creators simultaneously.

Roblox and Minecraft together represent over 300 million monthly active users building, modifying, and sharing interactive experiences. That’s the metaverse. Not a VR headset. Not a corporate rebrand. Platforms where imagination composes into shared reality.

From Language Models to World Models

Now layer on what happened in January 2026.

Google DeepMind released Project Genie — an AI system that generates navigable interactive 3D environments from text prompts. You describe a world; you walk through it. It’s limited: 60-second experiences, 720p, 24 FPS, no complex mechanics. Game developers called it everything from a tech demo to an abomination. The market, characteristically, saw something the developers missed. Unity dropped 30%. Roblox fell 12%. Take-Two lost 9%.

A few weeks later, Unity’s CEO announced an AI beta for GDC March 2026 that will let people create full casual games using only natural language. No code. Just describe what you want.

Project Genie in its current form doesn’t threaten anyone. But it prefigures a trajectory that I’ve been writing about since the Semantic Programming piece in 2023, when I built a complete RPG in a single day at a hackathon using Claude’s 100K-token context window and natural language as the integration layer between subsystems. That was Software 2.0 applied to game creation — natural language replacing imperative code as the primary means of expressing interactive systems. Andrej Karpathy‘s vision made tangible: you describe the behavior, and the model compiles it into something that runs.

Project Genie extends that principle from code to entire worlds. It’s crude today. But the trajectory from “60-second walking simulator at 720p” to “playable casual game from a prompt” is much shorter than the trajectory from “no computers” to “Pong.” The hard conceptual work — turning language into interactive spatial experience — is done. What remains is engineering and iteration. And those scale on curves we understand.

In the same way that early language models in 2020 prefigured the agentic engineering workflows that now let a single person build a chess platform in a weekend, Project Genie prefigures a future where the creation of interactive worlds follows the same trajectory. Not imminently — Genie’s 60-second walking simulators aren’t unseating Unity or Unreal anytime soon. But the direction is unmistakable, and the pace of AI capability improvement suggests the gap between tech demo and viable tool is measured in years, not decades.

The connection to the creator economy framework is direct. Every creative industry moves through three eras: Pioneer, Engineering, and Creator. The explosive growth phase — where participation goes from thousands to millions — only happens in the Creator Era, when top-down tools let people work from vision to implementation rather than from infrastructure up. Game development has been stuck in the Engineering Era: powerful tools that still require specialized teams. Project Genie and Roblox’s 4D generation aren’t the Creator Era fully realized. But they’re the first credible demonstrations that the Creator Era for interactive 3D experiences is technically achievable, not just theoretically desirable.

And crucially, this is top-down. I’ve written about why game development succeeds when it’s top-down — when creative vision drives implementation rather than technology driving design. The blockchain gaming wave failed precisely because it forced developers into bottom-up infrastructure work: smart contracts, RPC servers, APIs. The velocity loop between idea and implementation stretched to months or years, and the games suffered for it. AI-powered creation inverts this. You start with what you want the experience to be. The AI handles implementation. The velocity loop collapses. That’s why it works.

Beautiful Cathedrals, Open Universes

Here’s where I want to challenge our industry a bit: not with doom and gloom, but with a question about ambition.

Ball’s data shows that gaming’s revenue has grown while attention has declined. The industry’s response, broadly, has been financial: private equity invested $161 billion in gaming M&A in 2025, with the $55 billion EA take-private as the landmark deal.3 Venture funding for new gaming companies fell 55%. The smart money is buying installed bases and optimizing cash flows, not funding the next generation of platforms.

That’s a rational response to the current competitive environment. But it’s not a sufficient one. Because the attention problem isn’t a marketing problem or a monetization problem. It’s a participation problem. Gaming is losing attention to media forms that give people more active roles: as creators, as participants, as agents in their own right.

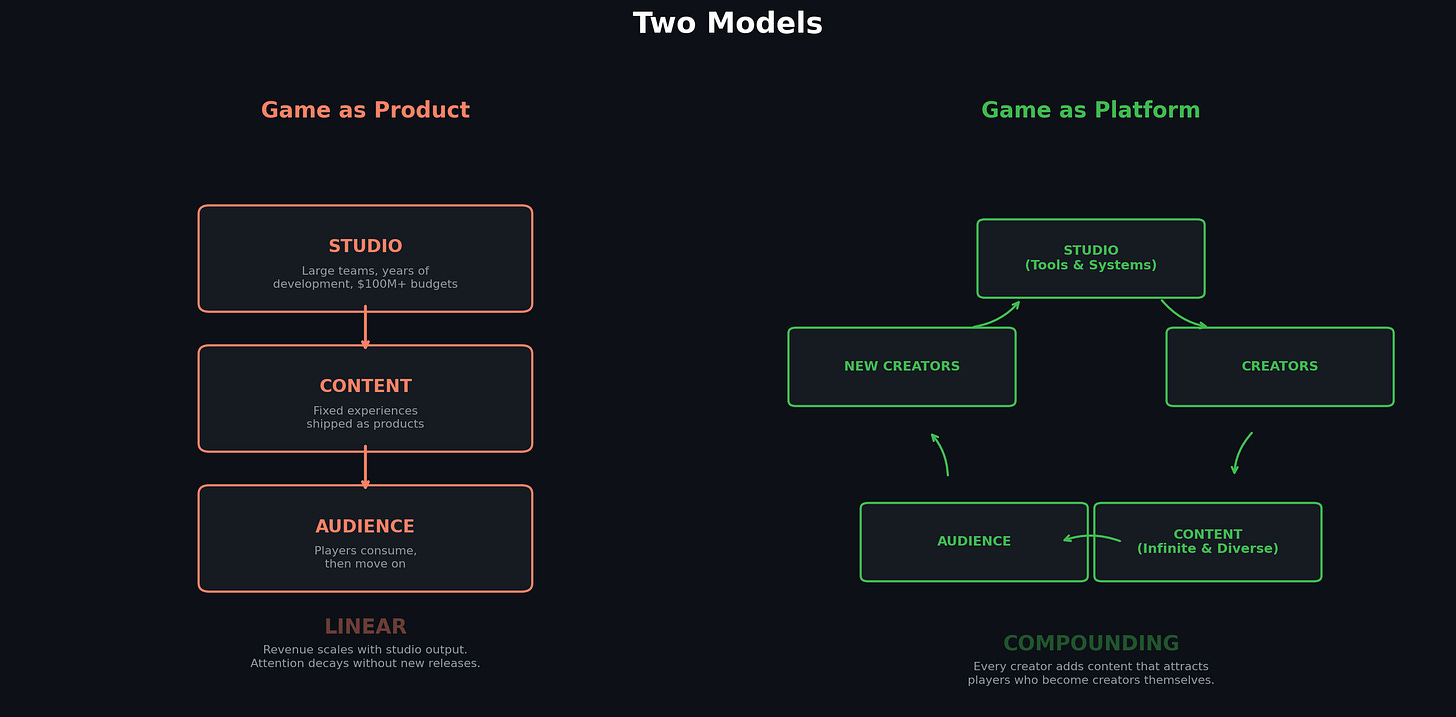

The fix isn’t to make better games in the traditional sense. The fix is to make games into platforms. To shift from building cathedrals that audiences visit to building universes that communities inhabit and extend.

Roblox understood this from the beginning. Their entire architecture assumes that the platform’s value comes from what creators build on it, not from what Roblox Corporation produces itself. That’s why their engagement is growing while the broader industry’s is shrinking. Every new creator on Roblox adds content that attracts more players who might become creators themselves: the composability flywheel I described years ago, where network effects compound through recombination.

Minecraft understood it too, in its own way. The modding ecosystem has always been Minecraft’s secret weapon, the reason the game has remained culturally relevant for over 15 years while most titles have shelf lives measured in months. The deobfuscation move is Mojang saying, explicitly, that they want to reduce the friction for creators even further.

But most of the games industry hasn’t made this shift. Most studios still think of games as products, not platforms. They build the content, ship the content, monetize the content, and then build the next content. The audience consumes. The studio produces. The loop is transactional.

I’ve been in this industry long enough to know that the talent in game studios is extraordinary. Ball’s own slide of 2025’s breakout successes makes the case: Kingdom Come: Deliverance II, Clair Obscur: Expedition 33, Split Fiction, Hollow Knight: Silksong — beautiful cathedrals, each one. Years of specialized craft producing singular experiences that millions of people loved. I’m not suggesting that craft doesn’t matter. It does. It always will.

But look at the same slide through a different lens. Schedule I and R.E.P.O., both made by tiny teams, both viral sensations—went supernova not just because they were good, but because they spread through participatory channels. TikTok clips, Twitch streams, community remixes. Their success was co-created by the audience. These aren’t anomalies. They’re early signals of a shift where leaner teams, armed with agentic workflows and AI-accelerated pipelines, will increasingly produce cathedral-quality experiences that once required hundred-person studios and publisher-scale budgets.

The beautiful cathedrals aren’t going away, they’re going to be built by fewer people, faster. And that changes the economics of the entire industry.

And then there’s INZOI, Krafton’s life simulator, quietly the most significant title on the list for this argument: because it’s not really a game-as-product at all. It’s a creation platform disguised as a life sim, where the core loop is building, sharing, and remixing player-made content. It’s closer to the Roblox model than the Kingdom Come model, and its presence among Ball’s top releases signals where the current is flowing.

The craft is real. But craft applied only to studio-produced content is a ceiling, not a trajectory.

The companies that will thrive in the next decade are the ones that take their craft and apply it to building creator ecosystems. That means rethinking not just how you make games—getting more efficient, building top-down, accelerating iteration through agentic processes—but how you open your games up to become actual platforms. Games-as-platforms. Universes that communities build on and around.

The difference between a game and a platform is the difference between making content and enabling composition. A game gives players something to do. A platform gives creators tools to build things that give other players something to do. The compounding effects of that distinction are what separate Roblox’s 69% DAU growth from the industry’s sub-pandemic engagement levels.

The Imagination Bottleneck

I keep coming back to a phrase from the Chessmata writeup: the bottleneck isn’t engineering capacity anymore. It’s imagination.

If that’s true — and everything from Roblox’s 4D generation to Unity’s AI beta to Project Genie suggests it is — then the strategic question for every game company shifts fundamentally. It’s no longer “how do we build this experience?” It’s “how do we build a system where millions of people can build experiences?”

The tools are arriving. AI-powered creation from natural language prompts. Foundation models that generate interactive 3D objects with behavior and physics. Agentic assistants that debug, optimize, and extend creator projects autonomously. MCP-connected design pipelines that bridge imagination to implementation without requiring creators to understand the underlying systems.

The creator platforms are proving the model works at scale. Roblox’s financial trajectory — $8.5 billion in bookings guidance for 2026, $1.8 billion in free cash flow — isn’t a fluke. It’s the economic signature of a platform that’s entered the Creator Era while the rest of the industry is still optimizing the Engineering Era.

And the competitive landscape is making the urgency clear. Every hour a potential creator spends on TikTok, on prediction markets, on memecoin speculation, on iGaming — that’s an hour they’re not spending building interactive experiences. Not because those alternatives are better, but because they’re easier to participate in. They have lower barriers to entry. They close the loop between intention and action faster.

Gaming has something none of those alternatives offer: the richest, most expressive creative medium humans have ever built. The ability to craft worlds, tell stories, build systems, create shared experiences that connect people across time and space. That’s not a small thing. In my Gamescom talk, I called it the future of civilization, and I meant it.

But that richness only matters if people can access it. If it stays locked behind years of engine expertise and million-dollar budgets, the attention will continue migrating to platforms that prioritize participation over production values.

The metaverse we have isn’t the one anyone predicted in 2021. It’s not VR headsets and corporate virtual offices. It’s Roblox, Minecraft, and the emerging platforms that let people compose interactive experiences from imagination and shared tools. It’s messy, imperfect, and far more alive than any top-down corporate vision could ever be — because it’s built by millions of people, not a few thousand engineers.

The distinction this article draws—games as products versus games as platforms—isn’t a prediction about some distant future. It’s a description of a split that’s already happened.

On one side, an industry hitting record revenue while losing attention, consolidating through financial engineering, and building beautiful cathedrals with shrinking teams. On the other side, platforms where 300 million people build, share, and remix interactive experiences every month, powered by AI tools that are collapsing the distance between imagination and creation.

Both sides will continue to exist. But only one of them is growing. The question for the rest of the industry is which side you’re building for.

Further Reading

Matthew Ball’s State of Video Gaming in 2026: the full 164-slide analysis, including detailed data on attention migration, revenue concentration, and the competitive dynamics discussed throughout this piece.

Composability is the Most Powerful Creative Force in the Universe; my earlier essay on why recombination and composition always outpace individual creation, and what that means for designing platforms and creative ecosystems.

Game Development is Top-Down: the case for why creative vision must drive implementation rather than the reverse, and how the Pioneer → Engineering → Creator framework applies to game development specifically.

Chessmata: An Agentic Chess Platform, Built by Agents: a recent case study in building a complete multiplayer platform in a weekend using agentic engineering, demonstrating the shift from engineering bottleneck to imagination bottleneck.

Roblox Accelerating Creation with the Cube Foundation Model: Roblox’s announcement of 4D generation and the Cube Foundation Model, the most concrete demonstration of AI-powered creator tools at platform scale.

Google DeepMind: Project Genie: the research behind text-to-interactive-world generation that crashed gaming stocks and signaled the trajectory toward AI-native world building.

Neal Stephenson coined “metaverse” in Snow Crash in 1992, but the mechanics he described (persistent shared worlds, player-constructed spaces, portable identity) were already 18 years old. The original 1974 Dungeons & Dragons boxed set included rules for constructing fortifications and establishing baronies. Gygax’s Dungeon Master’s Guide (1979) was explicit that the game was designed not for one-off sessions but for campaigns: persistent worlds with continuity, shared economies, and player agency over the environment itself. The terminology didn’t exist yet, but the architecture did. I wrote about this in The Direct from Imagination Era Has Begun.

For non-developers: Minecraft’s Java Edition source code has been publicly available for years, but every variable and method name was scrambled into meaningless strings, a process called obfuscation. A class representing a Creeper enemy might appear as brc; its explode method as a; its fuse timer as ab. The modding community maintained volunteer-built translation maps, projects like MCP and Yarn, that took weeks to update after every game release. Mojang shipping fully readable code eliminated that entire bottleneck. Fabric published migration guides within 30 days. It’s the equivalent of a government declassifying its own archives.

The EA deal is worth unpacking. PIF, Saudi Arabia’s $941 billion sovereign wealth fund, already held a stake worth roughly $5.2 billion before the acquisition. They’ll own 93.4% of the company post-close, with Silver Lake at 5.5% and Affinity Partners at 1.1%, carrying $20 billion in debt financing from JPMorgan Chase. As have noted, serving the massive debt will require substantial financial optimization. PIF’s gaming portfolio now spans Capcom, Nexon, Nintendo, Take-Two, Scopely, and the world’s largest esports company: part of what the Sovereign Wealth Fund Institute’s president characterized as Saudi Arabia’s strategy to diversify away from fossil fuels. When gaming becomes a geopolitical asset class, the incentives shift from “make great games” to “optimize returns.”