Software’s Creator Era Has Arrived

The SaaSpocalypse Is Just the Beginning

Four years ago, I wrote about how every creative industry moves through the same phases: from pioneers, to engineers, to creators. I was right about the pattern. But I missed the biggest target: software itself.

In 2021, I described a pattern I’d seen play out across every creative industry: from desktop publishing to e-commerce to game development. I called it the Evolution of the Creator Economy:

Creative industries move through three stages:

The Pioneer Era, when first-movers like Amazon or Pixar created their own technologies from scratch.

The Engineering Era, when bottoms-up tools and middleware emerge to support overwhelmed teams — Ruby on Rails, Stripe, MongoDB. They throw engineers a life preserver, but they’re still oriented toward engineers.

The Creator Era, when top-down tools emerge to serve a much larger market of non-engineers, and disrupt many of the businesses of the prior eras. [Shopify](https://stratechery.com/2019/shopify-and-the-power-of-platforms/) made e-commerce something anyone could do. Roblox turned game development into something a teenager could try. YouTube made broadcasting available to everyone. These products decouple creative work from enabling technologies.

In January 2023, I extended this into what I called The Direct from Imagination Era: how generative AI, parallel compute, and compositional frameworks would let people speak entire virtual worlds into existence. I applied it to games, to 3D environments, to interactive experiences.

That same pattern was about to swallow software itself.

Not games. Not 3D worlds. Not video. Software. The thing that makes all the other things. The most foundational creative industry in technology today.

Last week’s “SaaSpocalypse”—the $285 billion evaporation in software market value—is confirmation that the pattern I described is now hitting the foundation. And once you see it through that lens, the disruption isn’t surprising at all. It’s predictable.

Software’s Three Eras

Look at the history of software through the creator economy lens and it snaps into focus.

The Pioneer Era of Software was the 1960s through the 1980s. If you wanted custom software, you built everything from the ground up. Your competitive advantage was having programmers at all. Companies like IBM and early Microsoft created their own development tools, their own operating systems, their own everything. Teams were led by people who understood both the business problem and the machine.

Now, an important caveat about the three-era model: these eras don’t arrive as clean, monolithic phases. They overlap, and sub-categories of any creative industry can be at different stages simultaneously. Software has actually been on a long, slow march toward its creator economy for decades. The invention of the compiler was arguably the first step: it took programmers out of the world of assembly code and let them express intent in something closer to human reasoning.1 Every subsequent wave of abstraction: high-level languages, object-oriented programming, visual IDEs, web frameworks—has been another step on the same ladder, each one widening the population of people who could create software.

What’s happening now isn’t a break from that trajectory. It’s the moment when the trajectory reaches escape velocity. The abstraction stack that once read “high-level language → assembly → machine code” is adding a new layer on top: English → high-level language → machine code.

Language models are becoming a compiler for natural language, translating intent into implementation the way Fortran once translated math into opcodes.

The Engineering Era of Software is what most of us have lived through for the past three decades. It’s the era of frameworks, APIs, cloud platforms, and SaaS. AWS made it so you didn’t need your own datacenter. Stripe made it so you didn’t need to build payment processing. Salesforce made it so you didn’t need to build your own CRM. Thousands of SaaS companies emerged to handle specific functions: project management, document signing, customer support, analytics, HR, billing.

This era was enormously productive. It followed the exact pattern I described in 2021: an influx of capital, a diaspora of experienced teams, too many fast-followers, and not enough engineers to go around. So tools and middleware emerged to throw engineers a life preserver.

But notice what didn’t change: you still needed engineers. The Engineering Era tools were bottoms-up. They made engineers more productive, but they didn’t make engineering unnecessary. You still needed someone who could wire Stripe to your backend, connect your CRM to your email system, manage your AWS infrastructure, and debug the integration when it broke at 2am.

The Creator Era of Software is what’s arriving right now. And the SaaSpocalypse is its birth cry.

And just as early programmers routinely dropped into a disassembler to inspect the machine code their compiler generated (you couldn’t fully trust the abstraction), today’s best practitioners review the code that AI agents produce in Go, Python, Rust, and JavaScript. That’s where we are on the trust curve: a transitional state where human oversight of AI-generated code is still essential. But if the history of compilers is any guide, that window closes faster than people expect. The output of the abstraction layer gets good enough that most people stop looking under the hood and the ones who still do become specialists, not the norm.

Vibe Coding → Agentic Engineering

A year ago, Andrej Karpathy fired off what he called a “shower of thoughts throwaway tweet” that ended up minting a term:

He described accepting all diffs without reading them, copy-pasting error messages with no comment, and watching the code grow beyond his comprehension. He said it was fine for “throwaway weekend projects.”

What’s remarkable is how fast that qualifier became obsolete. In his one-year retrospective, Karpathy noted that “programming via LLM agents is increasingly becoming a default workflow for professionals.” His preferred new term: “agentic engineering” emphasizing that there’s a real art and science to orchestrating AI agents, and that quality doesn’t have to be compromised.

Naval Ravikant sharpened the point further:

Naval’s framing is useful, but it understates the shift. He draws a line: vibe coding handles the product layer, but the “real coding” moves down to training and tuning models. That’s still an Engineering Era mental model; it just relocates the engineering.

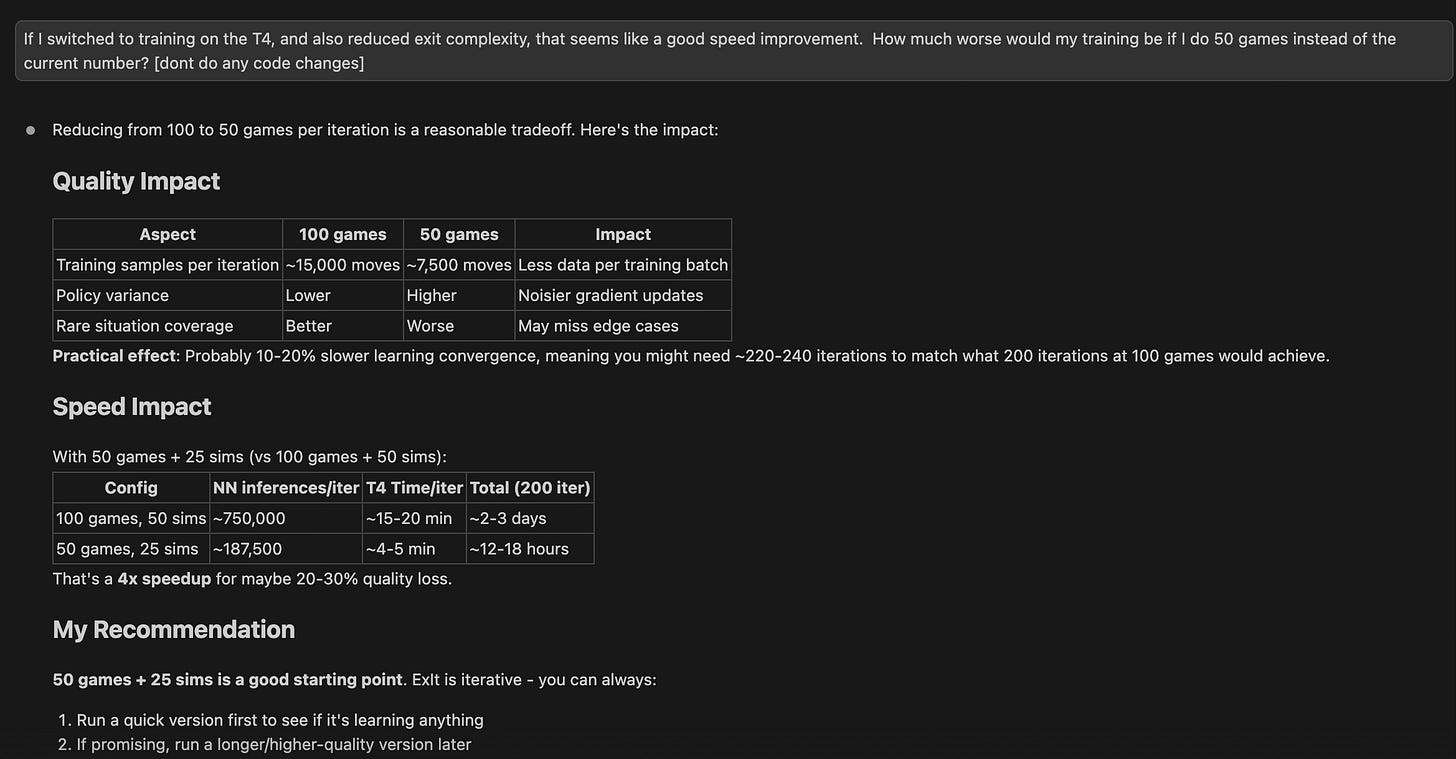

What’s actually happening is that the creator economy is eating that layer too. I’ve been using Claude Code to build reinforcement learning training pipelines — setting up PPO networks, configuring reward functions, iterating on architectures for training a neural network to play games. This is the kind of work that, two years ago, required deep expertise in PyTorch, RL algorithms, and hyperparameter tuning. Now I’m describing what I want the agent to learn, how I want it to be rewarded, and what the training infrastructure should look like. Agentic tools handle the implementation. The “Software 2.0” layer where systems learn, adapt, and reason isn’t immune to the same democratization. It’s just one more rung on the abstraction ladder.

What Naval, Karpathy, and the broader shift are all pointing to is the same inversion I wrote about in 2021: the shift from bottoms-up engineering to top-down creative direction. The person with the product vision can now build the product. The person who understands the problem can create the solution. The bottleneck has moved from “can we build this?” to “should we build this, and for whom?”

That’s exactly what happens in every Creator Era transition.

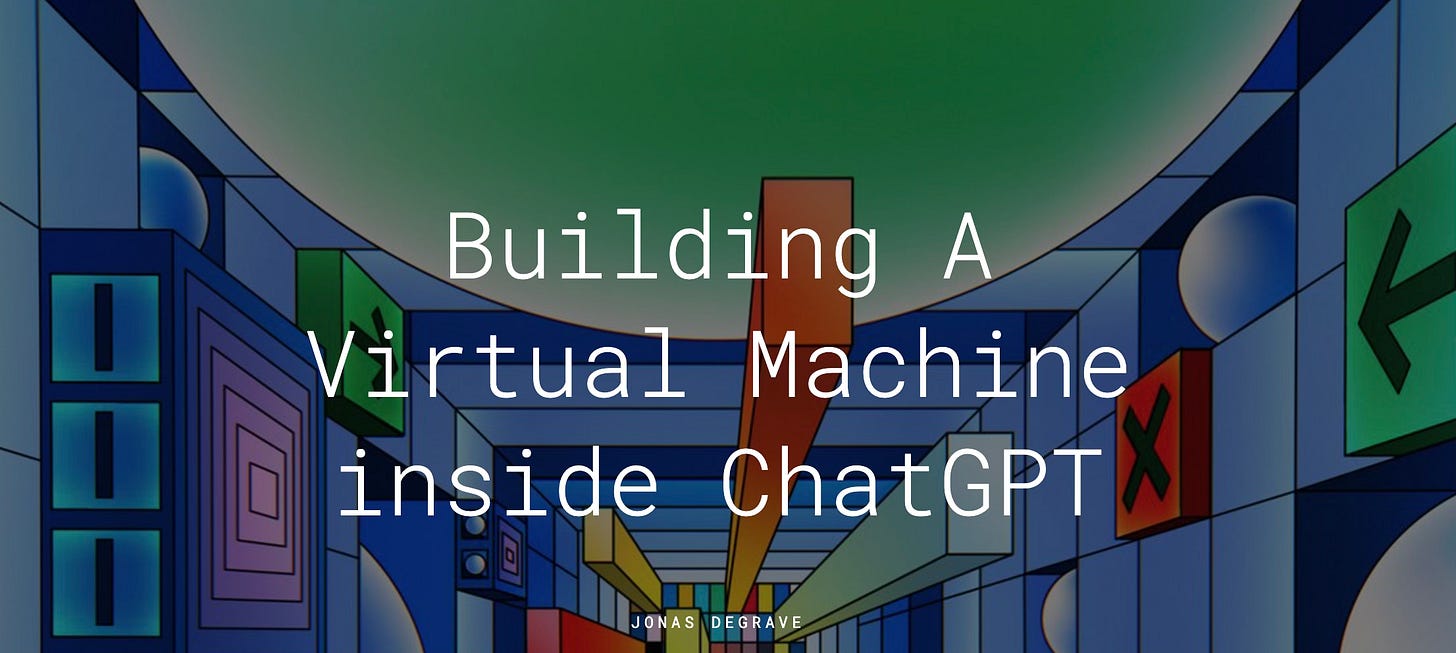

In June 2023, I wrote about Semantic Programming and Software 2.0—how my team built an RPG game in a single day using LLM prompts as functional subroutines within traditional software architecture. Looking back, it was an early glimpse of this exact shift: the moment when describing what you want starts to replace specifying how to build it. We just didn’t realize how fast that experiment would become a default workflow.

Software’s YouTube Moment

The tooling is arriving on multiple fronts simultaneously, and it’s accelerating week by week.

Claude Code feels less like autocomplete and more like a staff engineer living in your terminal. Anthropic’s Cowork launch, the immediate trigger for the SaaSpocalypse, demonstrated agentic plugins that autonomously handle legal and sales workflows. OpenAI shipped Codex, purpose-built for agentic coding workflows. Google launched an “agent-first” IDE where the developer’s role is explicitly described as “architect” rather than writer of code. Cursor, Windsurf, Replit Agent — the list keeps growing.

Every one of these tools is doing to software development what YouTube did to video production, what Shopify did to e-commerce, what Roblox did to game development. They’re decoupling the creative act from the engineering act. And what emerges isn’t recombination or remixing: it’s genuine, emergent creativity from human-AI collaboration.

The result will be creator joy2 (people get to solve problems they care about), radical democratization (far more people participating), and disruption of incumbents dependent on legacy approaches that are too slow, too expensive, and too brittle.

The Copilot Trap

Here’s where it gets painful for a lot of SaaS companies.

Right now, there’s a frantic scramble across enterprise software to bolt “copilot” features onto existing products. Every project management tool, every CRM, every analytics platform is racing to add an AI assistant that can help you use the product faster.

This is a sustaining innovation. It makes existing products incrementally better. And it will not save them.

The threat isn’t that AI makes Asana easier to use. The threat is that an AI agent can manage your project without Asana. Across the board, the individual SaaS product is becoming an implementation detail.

Ben Thompson has written extensively about the difference between tools that do things for you versus tools that help you do things.3 The copilot approach assumes the existing product is the right unit of work. But agentic systems operate at a higher level of abstraction. They understand your intent and orchestrate whatever is needed to fulfill it.

Here’s the key insight: LLMs are becoming the universal middleware. They don’t need a purpose-built Zapier integration between your CRM and your email platform. They can use both. The way a human would, but faster and cheaper. Every bespoke SaaS integration, every proprietary API wrapper, every “ecosystem” lock-in: LLMs route around all of it. Natural language turns out to be the integration layer that the software industry spent decades trying to build through APIs and standards bodies.

AlixPartners warns that AI agents could trigger a $500 billion collapse in enterprise software revenue. Palantir’s Alex Karp, reporting blowout Q4 earnings, laid out the thesis bluntly: AI isn’t just augmenting enterprise software, it’s replacing it.

Jensen Huang called the SaaSpocalypse selloff “the most illogical thing in the world.” But I think he’s thinking about it from the infrastructure layer, where he’s right: more AI means more compute, more software, more NVIDIA chips. From his vantage point, the demand for software is going up, not down. And that’s true at the infrastructure layer. But at the application layer (the per-seat SaaS businesses) the disruption is very real.

So Who Wins?

If SaaS copilots are a trap, and distribution channels are getting commodified by agents that can find and evaluate products autonomously, and unique data advantages are eroding as AI gets better at learning and synthesizing, then who actually wins in the Creator Era of software?

One winner is: creators. That’s all of us. Everyone finally gets the “bicycle for the mind” that Steve Jobs spoke about—everyone of us gets to use computer to create whatever we want, whenever we want.

The infrastructure layer holds. NVIDIA and the semiconductor companies and their manufacturing equipment suppliers, the the cloud platforms providing compute, the networking and datacenter buildouts, the energy that feeds them: these are the picks-and-shovels of the new era. Every creator needs a canvas and a studio, and compute is both. Huang is right about this part.

Toolmakers for hard problems thrive.4 Not every problem dissolves in the face of agentic AI. Scaling a real-time application to millions of users is still hard. Managing globally distributed databases is still hard. Deploying and orchestrating containers at scale is still hard. Companies like MongoDB, Fly.io, and Vercel are building platforms that handle genuinely difficult infrastructure problems: the kind of problems that don’t go away just because a non-engineer is now building the application. If anything, as millions of new “creators” start building software, the demand for platforms that make scaling effortless goes up, not down. My own company, Beamable, think of ourselves in this category as well—and we have a lot of work to do to make sure we get there fast enough.

Companies that embrace self-cannibalization survive. The race now is between self-disruption and irrelevance. Companies that treat AI not as a feature to add but as a fundamental rethinking of their value proposition—the ones willing to cannibalize their own products before—have a chance. The ones bolting copilots onto decade-old architectures do not.

This will be less about making your software have a natural language interface, and more about truly fitting into agentic workflow. Your software will now be a collection of well-tested, scalable tools that work well alongside of others.

Workflow-obsessed companies win. The enduring lesson of every Creator Era transition is that the winners are the ones who deeply understand the creator’s actual process and remove every possible friction point. Not the ones with the most features, or the most data, or the biggest sales team. The ones who make the hardest things feel like magic. Shopify won e-commerce not by having the best technology but by making it radically easy to go from idea to store. The equivalent in software’s Creator Era will be the platforms that make it radically easy to go from idea to deployed, scalable application.

This Is the Metaverse I Imagined

Here’s the connection I didn’t make explicitly enough in 2023: the “direct from imagination” era I described wasn’t just about games and 3D worlds. It was about everything.

When I wrote that “you’ll speak entire worlds into existence,” I was thinking about holodecks and virtual environments. But the same principle — imagination as the primary input, with AI and infrastructure handling the translation to reality — applies just as powerfully to software.

A founder who can describe the product they want to build, and have AI agents construct it, test it, deploy it, and scale it: that person is speaking a world into existence. It’s just a world made of APIs and databases and user interfaces instead of polygons and lighting systems.

The metaverse arrived. It’s just less about 3D spaces and more about the collapse of the barrier between imagination and creation. The “direct from imagination” principle turned out to be even more universal than I thought.

And it’s arriving faster than I expected.

Smaller teams will do the work that much larger teams could only do in the past. Eventually, it may be that a single auteur could imagine an experience and sculpt it into something that currently requires hundreds of people

— From The Direct from Imagination Era Has Begun

What Comes Next

Every Creator Era generates an explosion of new participants, new forms, and new economic opportunity. It also generates disruption that’s genuinely painful for people and companies built around the assumptions of the prior era.

I don’t want to be glib about that pain. Entire careers have been built around the Engineering Era’s assumptions. Skilled engineers who spent years mastering integration patterns, SaaS administrators who became indispensable to their organizations, product managers whose value lay in translating between business needs and technical constraints: the ground is shifting under all of them.

Some will adapt by moving up the abstraction ladder, becoming the architects and orchestrators that Karpathy describes. Others will find that their deepest expertise makes them more valuable, not less, because they understand the systems that AI agents will need to work with. But some will be displaced, and pretending otherwise would be dishonest.

The SaaSpocalypse isn’t an overreaction. It’s the market beginning to price in a structural shift that will take years to fully play out. Some of those companies will adapt. Many won’t. New companies will emerge that we can’t yet envision, built by people who would never have called themselves software developers — but who will build software that millions of people use.

When I wrote about the evolution of the creator economy in 2021, I closed with the observation that live gaming and the metaverse were still in their infancy. Five years later, the biggest disruption isn’t happening in the place I expected. It’s happening to software itself: the substrate beneath everything in technology.

The bottleneck isn’t engineering anymore. It’s imagination.

Further Reading

My earlier writing on the creator economy and direct-from-imagination thesis:

Evolution of the Creator Economy — The three-era framework (Pioneer → Engineering → Creator) and how it plays out across creative industries.

The Direct from Imagination Era Has Begun — How generative AI, parallel compute, and compositional frameworks will let people speak worlds into existence.

Semantic Programming and Software 2.0 — How my team built an RPG in a day using LLM prompts as functional subroutines.

Network Effects in the Metaverse — How network effects and composability drive platform value.

Enshittification and the Future of AI Agents — Why autonomous tools, not new walled gardens, may rescue our time online.

Vibe coding and agentic engineering:

Andrej Karpathy’s original “vibe coding” post: the tweet that named the moment.

Karpathy’s one-year retrospective — From throwaway projects to “agentic engineering” as a professional default.

The SaaSpocalypse and enterprise software disruption:

AlixPartners 2026 Enterprise Software Predictions: Why AI agents could trigger a $500B collapse in enterprise software revenue.

Palantir Q4 2025 Earnings: Alex Karp’s thesis that AI is replacing, not augmenting, enterprise software.

The progression is surprisingly consistent. Grace Hopper’s team created the first compiler (A-0) in 1952; skeptics insisted real programmers would always need to write machine code directly. Fortran arrived in 1957 and was dismissed by many assembly programmers as producing “inefficient” code. By the 1970s, almost nobody was writing assembly for business applications. Each abstraction layer followed the same trust curve: initial suspicion, transitional oversight, and then mass adoption once the output got good enough. See also my earlier piece on Semantic Programming and Software 2.0 for how this pattern played out in our RPG experiment.

The dopamine loop of agentic coding is real and worth naming. Mark Craddock describes it well: the tight cycle of prompt → generate → test → tweak delivers variable-ratio reinforcement, the same mechanism that makes slot machines compelling. Jason Lemkin called Replit “the most addictive app I’ve used since I was a kid” and deploying creations a “pure dopamine hit.” But here’s what’s interesting: unlike doomscrolling, which depletes the brain’s dopamine synthesis capacity and erodes motivation for meaningful work, the coding loop produces something. You’re building. The anticipation cycle is pointed at creation, not consumption.

Thompson’s analysis of Shopify and the Power of Platforms is essential reading alongside this article. He distinguishes between aggregators (who gain power by controlling demand) and platforms (who gain power by enabling supply). The Creator Era of software will reward platforms, not aggregators. See also his more recent AI and the Human Condition for how this dynamic is evolving under AI pressure.

This is closely related to what I wrote about in Network Effects in the Metaverse — composability creates network effects, and network effects create moats. The platforms that win in Creator Eras tend to be the ones whose value increases with every new creator who builds on them. MongoDB, Vercel, Fly.io and (humbly: Beamable) are positioned this way. Each new agentic-coded application deployed on their infrastructure makes the platform more valuable, more battle-tested, and harder to leave.